When faced with a supply chain disruption, proactive and reactive supply chain risk management can in fact make or break a company’s existence. One of the most famous (or rather infamous) cases is the fire at the Philips microchip plant in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 2000, which simultaneously affected both Nokia and Ericsson. However, both companies took a very different approach toward the incident, and in hindsight, clearly displayed how to and how not to handle supply chain disruptions.

When faced with a supply chain disruption, proactive and reactive supply chain risk management can in fact make or break a company’s existence. One of the most famous (or rather infamous) cases is the fire at the Philips microchip plant in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 2000, which simultaneously affected both Nokia and Ericsson. However, both companies took a very different approach toward the incident, and in hindsight, clearly displayed how to and how not to handle supply chain disruptions.

Ericsson’s downfall

I haven’t been able to find much research literature on Nokia’s supply chain risk management, maybe because it went so well for Nokia. Ericsson, on the other hand, is another story. The incident turned disaster cost the Swedish company $400 million in lost sales, and it had to quit the mobile-phone business, leaving Nokia to cement its position as the European market leader. What went wrong?

Ericsson vs. Nokia

In the late 1990s, Swedish-owned Ericsson was one of the big international players in the mobile phone industry, together with the Finnish company Nokia. My first mobile phone in 1996 was in fact a Nokia, but I switched to Ericsson in 1999, because they made much better phones, so I thought. While the phones may have been better, risk management for sure wasn’t.

The Albuquerque fire

On March 17, 2000, a small fire hit a microchip plant owned by Philips, the Dutch company. The plant supplied chips to both Ericsson and Nokia, and the smoke and water damage from the small and easily contained fire contaminated millions of chips — almost the plant’s entire stock.

Nokia verus Ericsson

Nokia acted swiftly and moved to tie up spare capacity at other Philips plants and every other supplier they could find. They even re-engineered some of their phones so they could take chips from other Japanese and American suppliers. Ericsson, meanwhile, had accepted early assurances that the fire was unlikely to cause a big problem, and settled down to wait it out. When they realized their mistake it was too late: Since Ericsson a few years earlier had decided to buy key components from a single source to simplify its supply chain, Ericsson now had to face the bitter realization that it had no other source of supply. Nokia had already taken it all. Single sourcing may have its benefits, but it has its costs, too. Ericsson lost many months of production, and hence many sales in a booming market that could now be dominated by Nokia. Bummer. Eventually Ericsson merged with Sony in order to survive, and eventually I too had to switch back to Nokia.

Day by day

Read a detailed account of the events in The fire that changed an industry, an article in the Financial Times.

Ericsson’s new approach

Ericsson learned its lesson and now has a completely different supply chain risk management system in place. It starts with mapping all the components and and products many tiers upstream the supply chain and identifies critical suppliers and sites that have to be prioritized and assessed further. After a rough assessment on how shortage will affect the supply chain, a more thorough investigation into probability and impact of different accidents at different suppliers is conducted to assess the impact on the supply chain as a whole, particularly the impact on business recovery time. Finally, risk management actions (protection) are evaluated against risk costs (impact and consequences), to avoid over-action or over-insurance against incidents.

Lessons learned

Not only Ericsson, but many other companies have also learned from this incident. Supply chain risk management (SCRM) is a necessary component of any supply chain. SCRM may lead to increased costs in the from of prevention measures, and SCRM may lead to increased lead time, in order to have buffers, should something happen. In essence though, risk exposure always has a price, and as a company one should think through what price (or rather cost, as in disruption cost) that is acceptable or not.

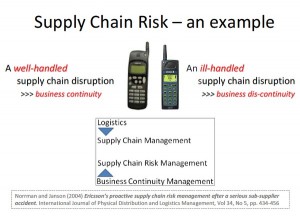

A well-handled supply chain disruption equals business continuity; An ill-handled supply chain disruption equals business dis-continuity.

In his 2006 article Robust strategies for mitigating supply chain disruptions, Christopher Tang uses Nokia’s approach as one of three prime examples of how to counter supply chain disruptions. Most recently Jon Hansen of Procurement Insights decided to reopen the case and ask industry experts to weigh in with their opinion as to what happened at Ericsson and why, and what they believe should take place to address the obvious shortfalls on a go forward basis.

Lessons not learned

This article was written in 2004, when Nokia was still a major player in the mobile market. While Nokia may have learned a lesson in supply chain resilience, Nokia did not learn what it would have taken to stay a major player.

That is unfortunate, because Nokia phones have always been my favourite, and I would have loved to see Nokia continue making phones. I’ve held on to Nokia as my mobile phone supplier as long as I could, and I still do: I carry a Nokia Lumia (now Microsoft) with me.

References

Norrman, A., & Jansson, U. (2004). Ericsson’s proactive supply chain risk management approach after a serious sub-supplier accident International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 34 (5), 434-456 DOI: 10.1108/09600030410545463

Latour, A. (2001). Trial by Fire: a blaze in Albuquerque sets off major crisis for cellphone giants. The Wall Street Journal, January 29, 2001.

Author links

- lth.se: Andreas Norrman

- linkedin.com: Ulf Jansson (perhaps?)

Links and more details

- ncsu.edu: How do suply chain disruptions occur?

- mit.edu: Big Lessons from Small Disruptions (pdf)

- Financial Times: The fire that changed an industry

- Times Online: Can Suppliers Bring Down your Firm?

Related posts

- husdal.com: Single or dual sourcing – which is better?

- husdal.com: The six ways of dealing with risk

- husdal.com: Risk Management – Contingent versus Mitigative