The risk management literature separates between mitigative actions or strategies and contingent actions or strategies. It is important to keep these two perspectives apart. Why? Because risk management needs to address both sides of the risk: what lies behind the risk (source) and what lies in front of it (consequences). Here is my attempt at defining these two terms and explaining the differences, at least the way I see it, based on Asbjørnslett (2008), Tomlin (2006) and Jüttner et al. (2003).

The risk management literature separates between mitigative actions or strategies and contingent actions or strategies. It is important to keep these two perspectives apart. Why? Because risk management needs to address both sides of the risk: what lies behind the risk (source) and what lies in front of it (consequences). Here is my attempt at defining these two terms and explaining the differences, at least the way I see it, based on Asbjørnslett (2008), Tomlin (2006) and Jüttner et al. (2003).

What is risk?

There are many many many definitions of risk in the literature, and will not attempt to list them all. Suffice it to say that I define risk as follows:

Risk is the exposure to circumstances with potentially damaging effects arising from an event that is not handled appropriately.

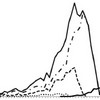

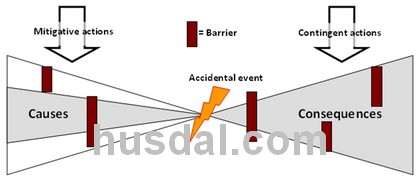

Risk management needs to address both sides of an accidental event, the sources leading up to it and the consequences arising from it. In figurative terms, “barriers” are put in place on both sides aimed at stopping a circumstance from evolving into an event, or aimed at stopping an event from developing disastrous consequences. Example: In a production facility running machinery that can overheat, a fire would be the accidental event, a heat detector would be a source barrier, while a fire sprinkler would be a consequence barrier.

The missing link

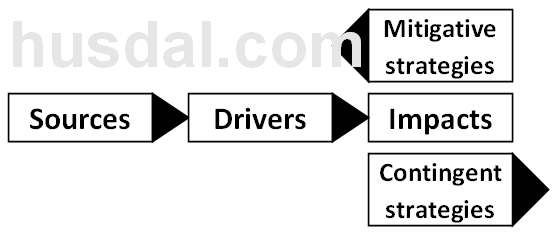

The idea for this post came while looking at Jütner, U., Peck, H., & Christopher, M. (2003) Supply Chain Risk Management: Outlining an Agenda for Future Research, where the authors look at risk sources, risk drivers and risk consequences. Here, risk mitigation is backward looking at sources and drivers, that is correct, but the contingent actions addressing the consequences are not fully embedded into their model. In the figure below I have attempted to illustrate how this can be done in a better way.

Risk sources need risk drivers to create risk impacts. Risk impacts are addressed by using mitigative strategies aimed towards eliminating the source or the driver, or contingent strategies, aimed towards eliminating the impacts. A similar notion, separating the cause and effect of risks, can be seen in the figures Holger Köhler uses in his PhD on Supply Chain Risks in Low Cost Country Sourcing.

Money matters

In On the value of Mitigation and Contingency Strategies for Managing Supply Chain Disruption Risks (Tomlin, 2006) there is a distinct difference between contingent and mitigative actions. Contingency action are actions taken in the event of a disruption, mitigation actions are actions taken in advance of a disruption. While the latter will incur a cost regardless of disruption, contingent actions will incur costs mainly in their preparation stage, and the again of course, if, but only if, they need to be taken.

Barriers, barrier, barriers

In Assessing the vulnerability of your production system (Asbjørnslett,1997), and later in Assessing the Vulnerability of Supply Chains (Asbjørnslett, 2008) there is a figure that excellently illustrates the difference between mitigation and contingency.

The figure above is my extension of the figure used in A.bjørnslett (1997) and Asbjørnslett (2008), capturing both contingent strategies and mitigative strategies. Here it is clearly seen that risk management needs to address both sides of the risk: what lies behind the risk (source) and what lies in front of it (consequences).

Conclusion

Hopefully this little discourse has clarified the difference between mitigative and contingent strategies. To understand concepts I find it most helpful to draw what I read, as I have with the two papers cited today. Well, actually, I did not draw everything entirely, I just expanded already existing figures. This (above) is how I view risk management, as an effort not just to reduce risk sources, but also as an effort to reduce risk impacts.

Update 2015

Mitigation, as I have looked at it so far, is mostly concerned with prevention. However, as I am now gradually discovering, based on Mattsson and Jenelius (2015) and their paper on transport network resilience and vulnerability, mitigation addresses the whole bow-tie, both the causes on the left side and the consequences on the right side. Resilience then, looks further to right of the bow-tie, and how the organisation tries to deal with the long-term impacts of an event. That is a new point of view that I hadn’t thought about, or rather, I had thought about it, but I haven’t able to put it into a figure as brilliantly as Mattsson and Jenelius have done in this paper. It appears to me now that the bow tie is only about preparedness, response, and recovery. By adding adaptation to those three we also add resilience.

Reference

Bjørn Egil Asbjørnslett (2008). Assessing the Vulnerability of Supply Chains In G. A. Zsidisin & B. Ritchie (Eds.), Supply Chain Risk: A Handbook of Assessment, Management and Performance. New York, NY: Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-79934-6_2

Asbjørnslett, B. E., & Rausand, M. (1997). Assess the vulnerability of your production system (Report No. 97018): Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

Jüttner, U., Peck, H., & Christopher, M. (2003). Supply chain risk management: outlining an agenda for future research International Journal of Logistics, 6 (4), 197-210 DOI: 10.1080/13675560310001627016

Tomlin, B. (2006). On the Value of Mitigation and Contingency Strategies for Managing Supply Chain Disruption Risks Management Science, 52 (5), 639-657 DOI: 10.1287/mnsc.1060.0515

Author links

- linkedin.com: Uta Jüttner

- martin-christopher.info: Martin Christopher

- linkedin.com: Helen Peck

- linkedin.com: Bjørn Egil Asbjørnslett

- linkedin.com: Marvin Rausand

- linkedin.com: Brian Tomlin