Is risk management overlooked as an important source of competitive advantage? That is the question sought answered by Donald Lessard and Rafael Lucea in their recent paper on Embracing risk as a core competence: The case of CEMEX. While the case itself is interesting, what the paper does highlight most is that instead of shedding risk, companies should accept risk as an opportunity. It should be welcomed, not feared. Why?

Is risk management overlooked as an important source of competitive advantage? That is the question sought answered by Donald Lessard and Rafael Lucea in their recent paper on Embracing risk as a core competence: The case of CEMEX. While the case itself is interesting, what the paper does highlight most is that instead of shedding risk, companies should accept risk as an opportunity. It should be welcomed, not feared. Why?

Exploiting risk – something new?

Exploiting risk as a risk management strategy is nothing really new. It appears already in the book by DeLoach (2000) Enterprise-wide Risk Management: Strategies for linking risk and opportunity, and I am somewhat surprised that this book does not appear in the reference list of this article. That said, the authors make a valid case for why risk is not something that should be shunned or avoided at all costs. Quite the contrary, it should be sought and shaped.

The four myths of risk management

The authors go straight to the point, arguing that blindly minimizing risk is a losing proposition in the long term, and that uncertainty or risk are at the root of opportunity towards new profitable enterprises. Risk minimizing does not equal profit maximizing. However, four myths stand in the way:

For risk management to become a tool to attain sustained advantage over one’s competitors, firms must challenge four deeply seated myths that color current research and practice. The first myth is that risk stems from various sources that are independent of one another. The second myth is that risk can be managed solely through financial instruments. The third myth is that “managing risk” can be separated from “managing the business”. Finally, the fourth myth is that all the risks a firm faces are constantly on the radar screen of top management teams.

Why do these myths need to be challenged? Because this new and radical conception of risk management, over time, will result in better business performance, so they say. Well, I think these guys are on to something here…

Myth 1 – Risk comes in bits and pieces

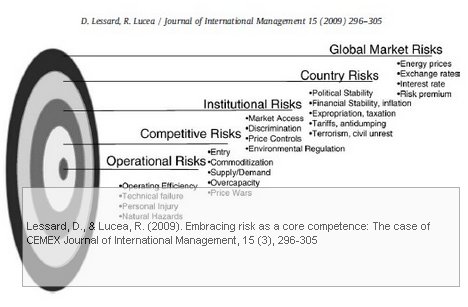

I have never given this much thought, but the authors are right. The risk literature tends to have a very piecemeal and myopic approach, looking at each risk one by one, and not in a coordinated and simultaneous fashion. Lessard and Lucea propose a risk taxonomy that classifies risks according to their nature and to the extent that they derive from managerial decisions or from forces that are beyond the control of the firm:

Operational risks have to do with what the company does and how it does it. Competitive risks are linked to the activities of direct competitors and other actors operating in one’s industry. Institutional risks are unexpected changes to the legal, normative, or social rules of how a firm is allowed to operate. Country risks have to do with more pervasive macroeconomic sources of uncertainty that are at work in a particular country. Global Market risks involve unexpected changes in global prices and worldwide availability of capital and basic commodities.

What the authors are saying is that firms face a broader array of risks than is commonly considered, that different sources of risk are not different, but interrelated, and that some risks are completely external to the firm, while others relate to directly to how the firm runs its operations.

Myth 2 – Risk is all about money

Unfortunately, instead of focusing on the risk itself, risk management (on the company-wide scale) has come to turn into a deployment of advanced financial tools to offset any risk associated with the business activities. There are three reasons for this:

because risks are seen as unconnected, financial instruments are generally designed to offset specific risks rather than system-wide risks

because of the sophistication of these financial instruments, the management of risk is often seen as the realm of a few highly specialized individuals or departments

because of the increased availability of financial instruments, risk management is ignoring the positive aspects of strategic decision making

However, as the authors clearly convey, risk management is not only about finance. Risk management means shaping the risk profile of the company and not only responding to the different sources of risk. Thus, risk management should take on a wide perspective. Nonethless, more often than not, in today’s businesses, there is a stark separation of those in the organization who “deal with risk” and those who “worry about growing the business”. Risk management needs to be deeply embedded in the culture of the firm and be reflected in its routines and coordinating processes and in the configuration of its value chain. Risk management is so much more than limiting the losses the firm might incur. That is one of the major messages in this article.

Myth 3 – Risk doesn’t concern me, but my boss

If risk management needs to involve all departments and individuals in an organization, it also mans that risk management cannot be solely a top management or a specialist task.

Acknowledging that some managers are in better position to respond to particular sources of risk does not imply that we are back in a situation where risks are thought of as bounded, independent and unconnected. It does imply, however, that very clear coordination mechanisms need to be set in place to avoid addressing a source of risk at one level of the organization while creating all sorts of other problems at another level.

What this means is that even if risk management decisions are made at a local or not so central level, it still needs to be a coordinated effort, in order to not propagate the risk to other and perhaps initially unrelated levels, as perfectly illustrated in the ponderings of Seu Keow Cheng and Booi Hon Kam in their tale of principals and agents: Cheng, S., & Kam, B. (2008) A conceptual framework for analysing risk in supply networks.

Myth 4 – Formalities and procedures work best

Traditional risk management relies heavily on formalized routines and structures for swift and efficient actions. The downside of these organizational procedures is that they constrain the scope of the problem and also delay or limit the solution process. Consequently,

as changes in the environment alter a company’s risk profile, company managers need to identify, make sense of and respond to the new scenario in an effective and efficient manner.

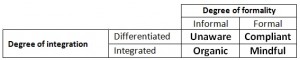

The authors then construct a framework for addressing risk along two dimensions: the degree of formality, and the degree of integration:

Firms that fall in the upper left quadrant (I) are, by and large, unaware of the risks they face and how they evolve. Firms that occupy the upper right quadrant (II) exhibit little integration of risk into their decision making but do establish formal mechanisms for addressing risk-related concerns. Firms that reside in the lower left quadrant (III) have typically developed organizational processes and tools that implicitly take risk into account but with little formalization of the concept or of associated processes. The lower right quadrant (IV) is home to firms that explicitly define the way they think about, measure, and integrate risk into the formulation and implementation of their business strategies.

I find this a very useful framework. On one hand it can be used to classify firms according to the general stance that they take toward risks. On the other hand it can also be used to describe how one particular firm addresses different types of risks. Risks that are inherent to the core activity of the firm will be treated in a formal and integrated manner. New and emerging risks are, at least at first, highly idiosyncratic and rarely linked to the core activity of the firm, and require an informal and differentiated approach, depending on the location and nature of the risk. The table also helps in tracing the evolution of a firm with regard to its risk management practices, where many firms tend to evolve from an Unaware or Organic to a Mindful position in the treatment of risk.

Conclusion

This is an excellent article. Although more geared towards risk management in general rather than supply chain risk management, in today’s business world, no company can exist independent of its supply chain, and anything that happens in the supply chain will sooner or later makes its way up to the board room. The article, and particularly the case (which I have not covered) shows how risk management can be used as a competitive tool. But only if risk-shedding is turned into risk-shaping. And only when firms evolve from haphazardly dealing with risk to fully exploiting and integrating it into their business management strategies.

Reference

Lessard, D., & Lucea, R. (2009). Embracing risk as a core competence: The case of CEMEX Journal of International Management, 15 (3), 296-305 DOI: 10.1016/j.intman.2009.01.003

Author links

- mit.edu: Donald Lessard

- gwu.edu: Rafael Lucea

Related

- husdal.com: Book Review: Enterprise-wide Risk Management

- husdal.com: The six ways of dealing with risk

- husdal.com: Risk in supply networks: A tale of principals and agents