In spite of all efforts to design safer systems, we still witness severe, large-scale accidents. A basic question is: Do we actually have adequate models of accident causation in the present dynamic society? That was the question asked by Jens Rasmussen in 1997 when he wrote Risk management in a dynamic society: a modelling problem. Here he argues that risk management includes several levels ranging from legislators, over managers and work planners, to system operators. Should supply chain risk management follow suit?

In spite of all efforts to design safer systems, we still witness severe, large-scale accidents. A basic question is: Do we actually have adequate models of accident causation in the present dynamic society? That was the question asked by Jens Rasmussen in 1997 when he wrote Risk management in a dynamic society: a modelling problem. Here he argues that risk management includes several levels ranging from legislators, over managers and work planners, to system operators. Should supply chain risk management follow suit?

Risks in a dynamic society

Rasmussen’s insights stem from his research in modeling industrial risk management, where he worked on systems and control engineering to design control and safety systems for hazardous industrial process plants.

An evaluation of our results in comparison with accident records rapidly guided our attention to the human-machine interface problems and we were forced to enter the arena of human error analysis, operator modelling, and display design, involving also psychological competence. From here, we quite naturally drifted into studies of the performance of the people preparing the work conditions of operators and we found it necessary to have a look at the results of research within management and organisational science also to consider the problem of decision errors at the management level. Finally, since a major problem appeared to be management’s commitment to safety and the related efforts of society to control management incentives by safety regulation, we also had to involve experts in law and legislation in our studies.

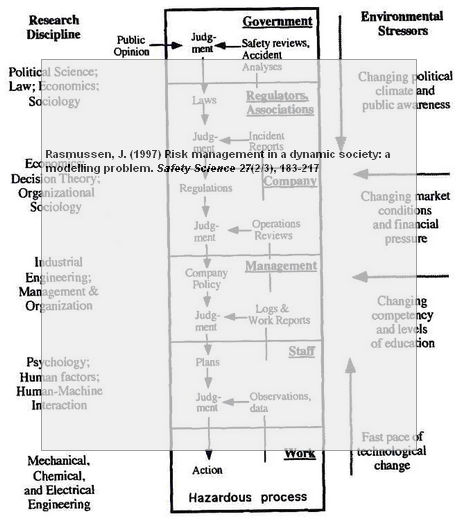

Safety is thus something that exists at the work environment level, but it’s implementation stems from directions at a higher level. Good safety management starts with good legislation, and with companies complying with regulations. But there is more to it, as the figure below shows:

At the top, society seeks to control safety through the legal system: safety has a high priority, but so has employment and trade balance. Legislation makes explicit the priorities of conflicting goals and sets boundaries of acceptable human conditions. Research at this level is within the focus of political and legal sciences. Next we are at the level of authorities and industrial associations, workers’ unions and other interest organisations. Here, the legislation is interpreted and implemented in rules to control activities in certain kinds of work places, for certain kinds of employees. This is the level of management scientists and work sociologists. To be operational, the rules now have to be interpreted and implemented in the context of a particular company, considering the work processes and equipment applied. Again, many details drawn from the local conditions and processes have to be added to make the rules operational and, again, new disciplines are involved such as work psychologists and researchers in human-machine interaction. Finally, at the bottom level we meet the engineering disciplines involved in the design of the productive and potentially hazardous processes and equipment and in developing standard operating procedures for the relevant operational states, including disturbances.

And Supply Chain Risk?

Does this have any relation to supply chain risk, you may ask? I think it does. I think supply chain risk management can follow suit here, certainly concerning the research disciplines on the left side. Supply chain risk management needs to involve more disciplines than management and operations. James Stock wrote about this in his article on applying theories from other disciplines to logistics in 1997, as did Michael Smith in 2005, when he suggested that supply chain management should borrow from other disciplines. The more research arenas that are drawn upon in risk management in supply chains, the richer and more fruitful the research and solutions will be that result from that. Logistics could become so much more.

Conclusion

This s a very theoretical article, not easy to read, nor easy to understand. Essentially, what Rasmussen tries to tell us is that risk management needs to be addressed (in different ways) at different levels, levels that are connected vertically and horizontally. While connected, they are also in conflict with each other, and decisions at one level may be offset by decision at another level, cancelling each other out. The problem lies in seeing the whole picture, and Rasmussen’s models go a long way in doing so.

This whitepaper based on Rasmussen’s work is actually a lot easier to understand than the original article: Proactive Risk Management in a Dynamic Society.

Reference

Rasmussen, J. (1997). Risk management in a dynamic society: a modelling problem Safety Science, 27 (2-3), 183-213 DOI: 10.1016/S0925-7535(97)00052-0

Author link

- wikipedia.org: Jens Rasmussen

Related links

Related posts

- husdal.com: Risk society