Accidents don’t just happen. They are a chain of critical events leading up to the disaster. Everyone who has watched an episode of the National Geographic Television series “Seconds from Disaster” will have heard that phrase. It’s the same with supply chain disasters; they are often the result of decision gone wrong and/or warnings not heeded. An insightful article in the Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, The Devil Lies in Details! How Crises Build up Within Organizations, by Christophe Roux-Dufort shows how organizational imperfections lay a favorable ground for crises to occur because managerial ignorance makes blind to the presence of these imperfections.

Accidents don’t just happen. They are a chain of critical events leading up to the disaster. Everyone who has watched an episode of the National Geographic Television series “Seconds from Disaster” will have heard that phrase. It’s the same with supply chain disasters; they are often the result of decision gone wrong and/or warnings not heeded. An insightful article in the Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, The Devil Lies in Details! How Crises Build up Within Organizations, by Christophe Roux-Dufort shows how organizational imperfections lay a favorable ground for crises to occur because managerial ignorance makes blind to the presence of these imperfections.

Crisis proneness

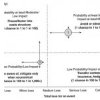

The article centers around the idea that crises build up from an accumulation of day-to-day imperfections that are small and unnoticeable (almost) and which progressively make the organization more vulnerable to any potential threats. The Devil lies in the details of these small anomalies (hence the title) and not in the sudden onset of exceptional events. Management is often oblivious to these small signals that something is out of order, or they focus their attention on the wrong anomalies. This is what Roux-Dufort calls crisis proneness, a combination of imperfections and managerial ignorance.

Crisis proneness

– an accumulation of imperfections

– an accumulation of managerial ignorance

Interestingly, Roux-Dufort notes that managerial ignorance is often caused by a manger’s effort to re-establish organizational stability by attacking these anomalies that threaten the manager’s self-esteem. This then becomes a defensive and reactive behavior rather than a proactive and offensive behavior, which could have averted the looming crisis.

Phases of crisis proneness

Crises, so Roux-Dufort, build up through four stages:

- Anomalies and inattention

- Vulnerabilities and attribution

- Disruptions and denial of reality

- Crisis and escalation

Imperfections accumulate and aggravate for each stage and managerial ignorance expresses itself differently in each of the four phases.

Anomalies and inattention

At the beginning, the signs of weakness are invisible and do not attract attention.

It is a door that remains open but that nobody notices because the importance of keeping the door closed either does not come into the manager’s field of attention or because it is an accepted part of the company’s culture. These are anomalies are so normal that they become invisible and perhaps even more so because they do not disturb normal operations. Taken to the extreme this ignorance sometimes leads to rationalizing and defending these imperfections as a condition for success and survival of the company.

However, this cannot go on for long, and only prepares the stage for the second phase.

Vulnerabilities and attribution

In the second stage, the anomalies are going to reoccur, develop and combine, leaving room for more salient imbalances.

If nothing is done to address the recurring anomalies, they will continue to build up to such a level that it cannot but raise a certain awareness among managers, because at least some part of the organization is disturbed by these anomalies, which often express themselves in incidents or near-accidents: individual conflicts, persistent rumours, stoppages, press articles, shares under pressure, an increase in customer complaints, loss of important contracts, recurrent quality problems, high staff turnover and alarming audits to mention a few. These vulnerabilities remain controllable, and because they are controllable they are not seen as existential threats. Often these events are attributed to a specific and plausible cause, often external, allowing for a sort of vindication and a temporary way out, blaming the unfortunate events on individuals or particular groups: journalists, trade unions, ministries or more abstract concepts like government policy, economic recession or extreme weather conditions.

In the end, this is only getting ever closer to the third stage, denial.

Disruptions and denial of reality

In the third stage the crisis starts to become visible.

Its starting point is often a more acute event than the others that uncovers the vulnerabilities and anomalies that have accumulated up to this point. It is at this moment that the disruption occurs, for which most of the time the procedures in place are incapable of providing a satisfactory response. In the previous stage, the incidents or dysfunctions often had a response in existing procedures; now there is no tool or procedures to handle the unfolding event in a definitive manner. This creates stagger, panic or temporary paralysis within organizations, because of the feeling of loss of control over what is happening. This is further escalated by hasty actions and reactions without first trying to understand the event: press conferences, setting up crisis management teams, invoking emergency plans and so forth. There is no time for analysis, there is only time for actions. The urgency to act takes precedence over everything else, and the previous reflexes of attributing and placing responsibility for the event with a number of actors and individuals is here an easy solution to use, but it only brings further denial of reality.

These convenient and hasty reactions leave no time for reflection over what is really brewing, namely the fourth and final stage, the crisis.

Crisis and escalation

The disturbance stage gives way to the crisis.

The disruptions leaves a gaping hole for the organization, its reputation and its management to be put into question. It is no longer about a disturbance but well and truly about a complete destabilization of the company and its environment. Previous ignorance only leads to escalation and strong counter-attacks: indictments, court actions, press conferences, and further denials.

Essentially then, crises are not exceptional events, but events that could have been averted, had the warnings not been ignored.

Conclusion

This is a very enlightening account of how crises from are seemingly small and insignificant anomalies. However, it does reflect much of what is said in the Harvard Business Review on Crisis Management, and the cases that were presented there. Christophe Roux-Dufort has actually written many articles and books on crisis management, and this is not the last time he will be on this blog.

Reference

Roux-Dufort, C. (2009). The Devil Lies in Details! How Crises Build up Within Organizations Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 17 (1), 4-11 DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00563.x

Author link

- EM Lyon: Christophe Roux-Dufort