Today I am taking a closer look at how buyer-supplier relationships evolve over time. This is the buyer-supplier relationship life cycle, where supply chains are dynamic and where supply chain partners are constantly changing: New suppliers are added, others are contractually terminated, cease to exist or become obsolete. Needless to say, nurturing and honing these relationships also improves supply chain performance. However, as Stephan Wagner points out in his recently published article on Supplier development and the relationship life-cycle, supplier development and supplier performance are dependent on the current stage or phase in the relationship life cycle.

Today I am taking a closer look at how buyer-supplier relationships evolve over time. This is the buyer-supplier relationship life cycle, where supply chains are dynamic and where supply chain partners are constantly changing: New suppliers are added, others are contractually terminated, cease to exist or become obsolete. Needless to say, nurturing and honing these relationships also improves supply chain performance. However, as Stephan Wagner points out in his recently published article on Supplier development and the relationship life-cycle, supplier development and supplier performance are dependent on the current stage or phase in the relationship life cycle.

Supply chain life cycle

Supplier relationships, supplier performance and supplier development have been mentioned on this blog on several occasions. Two years ago I wrote about a Norwegian PhD dissertation, where the author, Wei Deng Solvang, identified 5 phases in a supply chain life cycle:

1) identification of business opportunity, 2) selection of business partner, 3) formation of the supply chain, 4) operation of the supply chain, and 5) reconfiguration of the supply chain. This is a repetitive cycle. For every new business opportunity or product line these phases spring into action, thus creating a living and dynamic supply chain.

Solvang’s view on supply chains has much in common with what is known as Virtual Enterprise Networks (VENs), as described in The Networked Enterprise by Ken Thompson or in The Agile Virtual Enterprise by Ted Goranson, let alone in Creative Destruction by Nolan and Croson, all which have been included in my book chapter on managing risk in virtual enterprise networks.

Supplier development and supplier performance

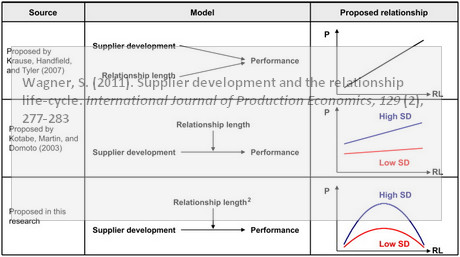

Wagner says that there are several approaches in the literature as to how supplier relationship length, supplier development and supplier performance come together. The dominant view is that of a linear relationship, where performance can only increase. The longer the relationship, the better the performance. However, if one takes the supply chain life cycle perspective into consideration, performance becomes convex, with a distinct peak and a following decline towards the end of the relationship:

Drawing on other researchers, Wagner states explicitly that

I argue that a more accurate model of supplier development activities should account for the life-cycle of the buyer–supplier relationship by including a squared term for relationship length as a moderator for the relationship between the buying firm’s supplier development activities and the improvement in the buying firm’s performance.

Buyer–supplier relationships are built up over time through legal, formal and informal exchange processes, and relation-specific investments. The relationship life-cycle influences the development of central relationship marketing constructs, such as cooperation, adaptation, information sharing, or commitment.

Supplier development will be more successful if the relationship is in a stage where the levels of cooperation, adaptation, information sharing, commitment, etc. are high (maturity) rather than low (initiation and decline).

Trust is a central organizing construct in buyer–supplier relationships. Trust builds slowly from experience as the relationship progresses and vanishes as the firms seek to leave the relationship.

For more reading on trust in business relationships I suggest Das and Teng (2001) on Trust, Control and Risk in Strategic Alliances, or Cousins (2002), who claims that all firms are snakes.

Relationship properties such as goal congruence, idiosyncratic time investments, idiosyncratic adaptation investments, willingness to take risk, or information exchange – are low in the exploration and decline phases of the relationship and high in the build-up and maturity phases. The effectiveness of supplier development activities will follow such a pattern of increase, zenith, and decline because many of these relationship properties are supportive or necessary for supplier development activities.

What Wagner means here is that supplier development activities must take into account at which stage or phase the relationship is, in order to be effective. Supplier development activities may even be counterproductive if forcefully applied too early or too late in the relationship:

In sum, in established buyer–supplier relationships, a buying firm’s supplier development activities will have the highest impact on its performance improvement. In contrast, supplier development in newer and older buyer–supplier relationships will be detrimental to the buying firm’s performance.

In other words, supplier development activities and supplier performance incentives are dependent on the current relationship life cycle phase. This means that the different stages in the supplier relationship life cycle should play an important role in determining how the supply chain can be improved.

Conclusion

This paper raises some interesting issues, particularly the question “Is supplier development always worth the effort?”. Obviously, as far as Wagner is concerned, it is not always worth the case. While I do agree that decreasing the effort towards the end of the relationship is the correct approach, I am more hesitant in concurring that supplier development activities that start too early are not effective. That said, it is worth to always consider the desired remaining length of the relationship before embarking on developing the supplier relationship.

Reference

Wagner, S. (2011). Supplier development and the relationship life-cycle International Journal of Production Economics, 129 (2), 277-283 DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.10.020

Author link

- linkedin.com: Stephan Wagner

Related posts

- husdal.com: All firms are snakes

- husdal.com: Supply Chain Life Cycle