Is culture shock the reason why so many global and cross-culture business relationships fail? When it comes to Western buyers and Chinese suppliers this may very well be the case, and while issues related to product quality or supplier reliability may seem as the obvious cause externally, cultural differences may be the root cause internally. Fu Jia and Christine Rutherford from Cranfield University have just published an article on Mitigation of supply chain relational risk caused by cultural differences between China and the West, where they claim that the extent of cultural adaptation between supplier and buyer is what makes or brakes global partnerships that are culturally different.

Is culture shock the reason why so many global and cross-culture business relationships fail? When it comes to Western buyers and Chinese suppliers this may very well be the case, and while issues related to product quality or supplier reliability may seem as the obvious cause externally, cultural differences may be the root cause internally. Fu Jia and Christine Rutherford from Cranfield University have just published an article on Mitigation of supply chain relational risk caused by cultural differences between China and the West, where they claim that the extent of cultural adaptation between supplier and buyer is what makes or brakes global partnerships that are culturally different.

New names, new topics

Christine Rutherford is not a new acquaintance, and albeit her writings have not yet been scrutinized on this blog, this being the very first time, I have come across her name every so often in my literature searches for articles on supply chain risk. Fu Jia is new to me, and as I discovered, much of the article is based on his PhD thesis with the same topic, Cultural adaptation between Western buyers and Chinese suppliers, available for download from the University of Cranfield.

Supply chain relational risk

The authors lament that much of the existing literature on supply chain risk is focused on the sources and mitigation of performance risks, like Peck (2006), while only very few have touched on the mitigation of relational risk, like Das and Teng (2001). That is why this paper focuses on a neglected area of supply chain risk, which they call supply chain relational risk (SCRR) and its mitigation. Jia and Rutherford define Supply Chain Relational Risk as

The risk to the supply chain of either party in a buyer-supplier relationship not fully committing to joint efforts due to either problems associated with cooperation or problems associated with opportunistic behaviour.

I think the key phrase here is not fully committing to joint efforts, as a supply chain can only work effectively if all members or parties are fully dedicated to making it work. What then is it that makes Chinese or Western businesses not fully commit?

Contracts versus connections

The basic cultural difference in managing supplier-buyer relationships between China and the West can be summarized by this: contracts (rules) versus connections (ties and networks) or “Guanxi”, as it is termed in Chinese. Guanxi is hard to explain and can best be described as

a special type of relationship that bonds the exchange partners through reciprocal exchange of favours and mutual obligations

Guanxi is a the root of all business transactions in China, something that is perhaps overlooked by many Westerners, beliveing that once a relationship has been established (with the help of a little Guanxi, or maybe not), it can then be governed by conventional contracts. Not so.

Cultural differences

The articles extends previous work by Jia and Rutherford, who identified nine supply relational risk sources by comparing cultural differences in the constructs of Western forms of supply relationship management and Guanxi, a Chinese form of relationship management. Unfortunately, these nine sources are not mentioned any further in this article, and to make it worse, this previous work is a conference presentation, and is thus practically impossible to get hold of. This is were Google came to my rescue, as it presented me with Fu Jia’s PhD thesis that forms the basis for the conference paper, and subsequently, for this article. After reading the nine differences I found them so fascinating that I will present them in detail in tomorrow’s post on the intricacies of Guanxi. Suffice it to say, and that is what this article has done, these nine differences boil down to three root causes of supply relational risk:

- Family orientation vs self-interest.

- Guanxi network vs multiple institutions-

- Guanxi building process vs Western relationship-building process.

The authors go on to describe these causes in more detail:

Collectivists, such as the Chinese, place group goals and collective action ahead of self-interest and gain satisfaction and feelings of accomplishment from group outcomes. In Chinese society, it is specifically the interests of the family that is put before individual interest. In the West, self-interest is more often than not put higher than group interest.

The Guanxi network or extended family network is probably the most important informal institution in the Chinese-speaking world. Respect for age, authority and social norms stem from the Confucian concept of li, which refers to rite and propriety in maintaining a person’sposition in the social hierarchy. Another major characteristic of Chinese culture is the maintenance of internal harmony, which is most likely to be achieved by compromising individual interests and choosing social conformity, non-offensive strategies and submission to social expectations. In the context of management, the Confucian li principle favours organizational hierarchy and centralized decision making, which means that the Chinese are more willing to recognize and accept a hierarchy of authority than their Western counterparts, as well as depending on the decision of their supervisors without question. In the West, people are governed by multiple institutions such as laws, regulations and procedures rather than hierarchy.

Models that describe relationship building in aWestern context are similar in that they define the sequential stages of an evolutionary process from initial partner contact through to commitment/dissolution. Chinese society places great stock on the importance of face (mianzi), which is an intangible form of social currency and personal status affected by one’s social position and material wealth, while renqing is first a set of social norms by which one has to abide in order to get along well with others in Chinese society; and second a resource that an individual can present to another as a gift in the course of social exchange. Relationship building in China is dominated by the forces of Guanxi and as such is informal, has a long-term orientation and is based on the interplay of face and renqing, i.e. it occurs at a personal level. In the West, the process of building a relationship has a short-term orientation, is more formal and based on the interplay of competition and cooperation, i.e. it occurs at a corporate rather than personal level.

How many businesses entering China for the first time do actually fully consider the above before engaging in business relationships with Chinese enterprises?

Mitigation strategies

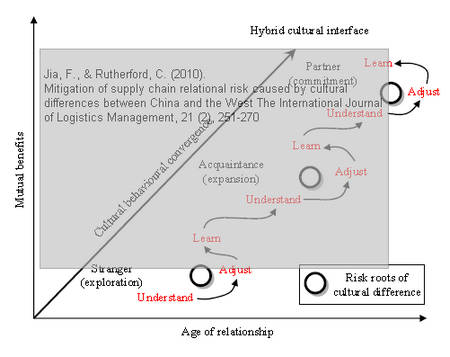

Jia and Rutherford propose inter-firm learning and cultural adaptation as two mitigation strategies to reduce the possibility of supply chain relational risk.

Cultural adaptation is put forward as the prime mitigation strategy, where the business partners go through stages of adaptation that converges their behavior through understanding, adjusting and learning, eventually leading to a mutually beneficial partnership between a buyer and a supplier of different national culture.

Critique

I found this a highly informative article for anyone thinking of entering a partnership with any kind of business in China, as this is an article that properly describes the pitfalls of Guanxi and how to avoid them, from an academic point of view, but not so academic that it cannot be read by the practitioner. The only downside I can find is the non-mentioning of the nine cultural differences so brilliantly described in Fu Jia’s PhD thesis, because I think they had deserved a place here, and not being aggregated into three sources. Well, for the curious reader, if you would like to know more, I will present them tomorrow.

Reference

Jia, F., & Rutherford, C. (2010). Mitigation of supply chain relational risk caused by cultural differences between China and the West The International Journal of Logistics Management, 21 (2), 251-270 DOI: 10.1108/09574091011071942

Author links

- exeter.ac.uk: Fu Jia

- cranfield.ac.uk: Christine Rutherford

Download

- cranfield.ac.uk: Cultural adaptation between Western buyers and Chinese suppliers (Fu Jia’s PhD thesis)

Related

- husdal.com: Trust, Control and Risk in Strategic Alliances