…what do you do? Is so-called supplier default something you have even thought about? And what if this supplier is connected to others such that if one fails, others may fail too, like an unstable house of cards? That is what concerns Stephan Wagner, Christoph Bode and Philipp Koziol in their 2008 article on Supplier default dependencies: Empirical evidence from the automotive industry, one of the few articles I know of that deals specifically with this topic. Based on empirical data from automotive suppliers, they reveal that default dependencies among suppliers do often exist and can have significant consequences.

…what do you do? Is so-called supplier default something you have even thought about? And what if this supplier is connected to others such that if one fails, others may fail too, like an unstable house of cards? That is what concerns Stephan Wagner, Christoph Bode and Philipp Koziol in their 2008 article on Supplier default dependencies: Empirical evidence from the automotive industry, one of the few articles I know of that deals specifically with this topic. Based on empirical data from automotive suppliers, they reveal that default dependencies among suppliers do often exist and can have significant consequences.

Predictable disruptions?

That one supplier takes another with him in the fall, like a chain of dominoes, should not come as a surprise, particularly not in the automobile industry, where one supplier may not only supply parts for different models of the same brand, but perhaps even supply parts for several models made by different car manufacturers. Many suppliers in the automobile industry are very much linked to each other, even though they may not realize it, and a car manufacturer who has spent time and effort in creating a diversified supplier portfolio may find that his portfolio is not so diversified after all, if it all falls apart just because one supplier defaults.

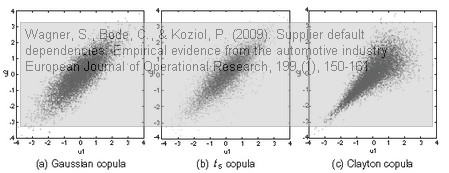

The copula approach

This is a highly empirical and analytical paper, and the core of model consists of copulas. A copula is a function that links univariate marginals to their full multivariate distribution. Thus, the marginal distributions and the dependence structure of the random variables can be modeled separately.

Copulas been extensively used for dependence modeling in finance-related problems. However, the authors note that

The selection of the appropriate copula is crucial. In this paper we highlight the flexible modeling using copulas and the consequences from different copula choices. The ultimate choice of the appropriate copula should reflect the dependence structure and risk profile of the supplier portfolio.

I must honestly admit that I do not fully understand the statistics and probability theory that works behind the scenes, which is why I will refrain from discussing it in this review, but I am able to appreciate the results.

Multi-sourcing does not equal redundancy in supply

What this paper tells is that simply adding more suppliers isn’t always better if safeguarding against disruptions is the objective:

From our analysis, several important implications for automotive OEMs in particular and buying firms in other industries in general can be derived. Most important, firms should revisit the commonly used ex-ante strategy of multiple-sourcing when aiming for a safeguard against the consequences of sudden supplier default, and take their suppliers’ default dependence into consideration. Purchasing managers should be aware that positive default dependence between suppliers is not an exceptional phenomenon. Therefore, our research questions the ‘‘hedging power” of multiplesourcing arrangements.

If a supplier portfolio analysis shows a hight default dependency among suppliers, there are several steps a buyer firm can take:

For single sourcing,

- Keep, but develop existing suppliers in order to increase their performance

- Switch to alternative, less default-dependent suppliers

For multiple sourcing,

- Create a portfolio of independent suppliers without ties to each other

The authors suggest that firms should align their supplier portfolio with the product development cycles and the life-cycles of their products on the market, which also reduces the probability of a supplier default spilling over from one product to the other.

Conclusion

As already mentioned, the paper is best suited for a reader with a quantitative mind, i.e. not me. That said, since I cannot vouch for the approach taken, the results speak for themselves. However, the data needed for running the analysis and simulations may not be easy to find, as

it requires market data – corporate bond data and corresponding market values in particular – to derive the suppliers’ individual default intensities.

Nonetheless, this paper shows that supply chain risk management must look beyond the individual supplier and look at dependencies within the entire supplier portfolio. Such dependencies may not be obvious at first sight, and this paper presents one very good approach towards discovering these dependencies.

Reference

Wagner, S., Bode, C., & Koziol, P. (2009). Supplier default dependencies: Empirical evidence from the automotive industry European Journal of Operational Research, 199 (1), 150-161 DOI: 10.1016/j.ejor.2008.11.012

Author links

- linkedin.com: Prof. Dr. Stephan M. Wagner

- linkedin.com: Dr. Christoph Bode

- linkedin.com: Philipp Koziol

Related

- husdal.com: Managing risk together