After studying supply chain risk research for some time I have begun to realize that much of the supply chain risk literature lacks direction and that each researcher or strand of researchers have their own presuppositions as to what supply chain risk is and how it should be addressed. In Knemeyer, A. M., Zinn, W. & Eroglu, C. (2009) Proactive planning for catastrophic events in supply chains, fortunately, there is a clear direction for further research and practical application as to how companies can evaluate and plan for catastrophic risk in supply chains.

After studying supply chain risk research for some time I have begun to realize that much of the supply chain risk literature lacks direction and that each researcher or strand of researchers have their own presuppositions as to what supply chain risk is and how it should be addressed. In Knemeyer, A. M., Zinn, W. & Eroglu, C. (2009) Proactive planning for catastrophic events in supply chains, fortunately, there is a clear direction for further research and practical application as to how companies can evaluate and plan for catastrophic risk in supply chains.

Key supply chain locations

As discussed in a previous post on facility location, finding the right facility location is difficult enough. Keeping it safe is even more difficult. One of the building bricks of the this article is the identification of so-called key supply chain locations, and the primary goal of the research in Knemeyer et al (2009) is

to propose a proactive planning process for addressing catastrophic risk in supply chains. This process should help managers identify key locations in their supply chains, systematically measure the risk of suffering a catastrophic event at each key location and then select cost effective countermeasures to be adopted at selected key locations.

What in each case that constitutes a key supply chain location is based on managerial judgment. It could be the single source for a raw material; it could be the main distribution center for a major market; it could be a public port or airport or other transfer points between transportation modes. The list is potentially endless, but any key location that can be easily circumvented or substituted is not a key location.

The proactive planning steps

The article proposes a 4-step process for risk assessment and and management:

- Identify Key Supply Chain Locations and threats

- Estimate Probabilities and Potential Loss for each Key Supply Chain Location

- Evaluate alternative Countermeasures for each Key Supply Chain Location

- Select Countermeasures for each Key Supply Chain Location

The Potential Loss is an important parameter here, and is defined as the product of the probability estimate of a catastrophic event at a key location with the estimated loss at the same key location:

PLk=Pk Lk

where Pk is the probability estimate of a catastrophic event impacting key location k, and Lk is the estimated loss that is incurred if an catastrophic event occurs at key location k.

Loss estimation

The ‘loss’ is much more than the physical assets, but it needs to be a cross-functional analysis of the catastrophic risk environment faced by each of the supply chain’s key locations:

- Human resources: death, injury, illness, kidnapping, etc.

- Product/inventory: theft, damage, contamination, lost sales, stockouts, etc.

- Physical assets: plants, warehouses, equipment, vehicles, etc.

- Public infrastructure: electric, water, gas utilities, bridges, ports, roads, etc.

- Information: loss of data, access, processing capabilities, etc.

- Financial: theft, counterfeiting, stock prices, etc.

The list implies that losses need to include tangible and non-tangible assets.

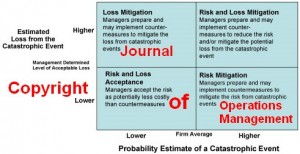

Risk management matrix

What I like about this paper is how they apply the traditional risk matrix within the setting of their own research, and how they clearly separate between risk mitigation and loss mitigation. Risk mitigation and loss mitigation are linked to the potential loss and estimated probability of a catastrophic event.

Click image for larger version

Click image for larger version

The reason for distinguishing between risk and loss becomes clear when one looks at the evaluation of countermeasures. While reducing the risks or estimated loss associated with a catastrophic event impacting a key location is normally considered beneficial, not every risk should be mitigated. In some cases, the costs of mitigation will be greater than the impact of the catastrophic event itself. Countermeasures whose costs exceed the decrease in PL should therefore be excluded from further analysis.

A typical example illustrating the above can be found in one of my previous articles on the ratio of cost/benefit versus vulnerability/reliability:

Click image for larger version

Here, point A indicates the costs of a supply chain disruption without mitigation. Provided some mitigation, the costs of disruption may be lowered, say, until point C. Too much mitigation may bring the disruption cost down to almost zero at point B, while the mitigation cost is much higher than the potential loss. Neither B nor C are optimal, although C is better than B. The optimum is reached where the cost of disruption intersects with the cost of mitigation.

Risk perception

Another interesting part of this article is the discussion on risk perception of catastrophic events among management at the beginning of the article. The reason why risk perception is important is because the probability of a catastrophic event occurring is very low, while at the same time the estimates of the probability of the occurrence for such rare events are inherently ambiguous. Risk aversion and loss aversion go hand in hand, and the question is whether managers will pay too little or too much attention to the low probabilities and high consequences associated with catastrophic events. When uncertainty is high, managers may underestimate the importance of an issue, and may – in the illusion of being in control – ignore or downplay the possibility of random or uncontrollable occurrences, and may downplay the probability of loss compared to the amount that is probable.

Cognitive dissonance

The theory of cognitive dissonance may also provide clarity regarding factors that influence a manager’s perceptions of the threat of catastrophic risks in their supply chain.

So supply chain managers may choose to accept the risk of a catastrophic event affecting their supply chain and choose to believe that this choice is not so risky. However, because this choice may ultimately prove to be costly based on the discrepancy between the belief and reality, any proactive planning process should enable management to utilize unbiased information to provide them direction in decision-making.

Teamwork

In their final paragraphs, ‘hidden’ among the implementation issues of the proactive planning process, the authors write that the key to manage catastrophic risk in supply chains is the people in charge of implementation. The proposed conceptual framework can only be converted into a proactive planning process if there are proper policies in place to recruit and motivate the implementation team.

The implementation team should be cross-functional because the consequences of catastrophic events cut across the supply chain. If, for instance, a facility is lost to a catastrophic event, the consequences affect supply chain operations, financial flows and possibly also information flows. It may additionally impact relationships with customers and suppliers. As a result, a wide spectrum of functional expertise is needed to foresee potential catastrophic risks and evaluate their likely consequences.

I said ‘hidden’, because to me, this is the most crucial part of managing catastrophic risk: people. the wrong people in the wrong place at the wrong time can make or break a company’s existence if a catastrophic supply chain event is not handled appropriately.

Reference

Knemeyer, A., Zinn, W., & Eroglu, C. (2009). Proactive planning for catastrophic events in supply chains Journal of Operations Management, 27 (2), 141-153 DOI: 10.1016/j.jom.2008.06.002

Author links

- osu.edu: A Michael Knemeyer

- osu.edu: Walter Zinn

- uark.edu: Cuneyt Eroglu

Related

- husdal.com: The six ways of dealing with risk

- husdal.com: Finding the right location – minimizing disruption costs

- husdal.com: Costs and benefits versus reliability and vulnerability