Purchasing theory… I have to admit it’s not one of my particular strongholds, but several of my readers and commenters have mentioned this article, most recently in a comment on A future research agenda for supply chain risk management, so I thought that perhaps I should have a look at it. After all, supplier relationships have been on my blog time and again , so why not? In their 2005 article Risk-based classification of supplier relationships by a Finnish quartet from the Lappeenranann University of Technology, Jukka Hallikas, Kaisu Puumalainen, Toni Vesterinen and Veli-Matti Virolainen set out to develop a new classification scheme for suppliers, based on buyer dependency risk and supplier dependency risk.

Purchasing theory… I have to admit it’s not one of my particular strongholds, but several of my readers and commenters have mentioned this article, most recently in a comment on A future research agenda for supply chain risk management, so I thought that perhaps I should have a look at it. After all, supplier relationships have been on my blog time and again , so why not? In their 2005 article Risk-based classification of supplier relationships by a Finnish quartet from the Lappeenranann University of Technology, Jukka Hallikas, Kaisu Puumalainen, Toni Vesterinen and Veli-Matti Virolainen set out to develop a new classification scheme for suppliers, based on buyer dependency risk and supplier dependency risk.

Organizational learning

How do risks in supply relationships and and organizational learning play out in risk management? The idea is that supply chain partners collaborate as a response to uncertainty in the supply and in consequence develop a learning supply chain, in which they share information. While collaboration obviously has a benefit, there is also the risk of collaboration partners behaving opportunistically, since all firm are snakes, according to Cousins (2002). Supplier risk management needs to balance both sides of the scale.

How to classify supplier relationships

The literature generally acknowledges two approaches, the continuum approach and the portfolio approach. The continuum model typically arranges suppliers along a scale or degree of collaboration, e.g. Kampstra et al (2006), while the portfolio model divides suppliers along types of items purchased, e.g. Kraljic (1983), which is a paper I have long planned to but never gotten around to review on this blog.

The supplier’s perspective

The portfolio model appears to be more widely used, so the authors say, but it has its limitations. Firstly, it can become very complex and difficult to manage if the number of against it is that it neglects the supplier’s perspective, i.e. before entering a relationship with a supplier, a company should also consider how this relationship will affect the supplier, something I find an interesting statement. But, there are reasons for why the supplier, not just the buyer, needs to be part of the equation.

Transaction cost economics to the rescue

Why is the supplier’s perspective important? Because supply chains are no longer chains, but a web of interconnected networks, where one depends on the the other(s), many depend on one, or many depend on many. A strand of purchasing and supply research that captures this is the transaction cost approach, where benefits and risks vary according to the type of business relationship.

Sources of risks

Hallikas et al define four groups of risks in a transaction cost context

- asset-specific “hold-up”-risk

- the higher the asset specificity, the greater the danger for opportunism

- market-related “inefficiency” risks

- the more buyer/suppliers there are, the lower the transaction cost

- knowledge-related “spill-over” risk

- the more appropriable new knowledge is, the easier it can be shifted from one to the other

- time-related “timing” risks

- the greater the difference in planning horizon, the higher the risks of networking

There are other risks in collaborative relationships, but the above are the most dominant.

Case study

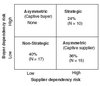

In a case study, involving a Finnish OEM, Hallikas et al found that supplier relationships fell into three clusters, as seen in he figure below.

Interestingly, none of the relationships were characterized by a high buyer, but low supplier dependency, meaning hat supplier can chose between buyers, but the buyer has only one supplier. This could be caused by the selection of suppliers, or it could actually be that this is the case in the real world. hat do you think?

Parameters used

What I found very interesting with this paper were the parameters or variables used to describe risks, organizational learning and risk management, in order to underpin the above framework.

- Risks

- Hold-up risk

- Demand risk

- Replaceability

- Risk management

- Measurement criteria

- Fault management

- Innovativeness

- Prioritization

- Protection of intellectual property

- Communication

- Learning

- Strategic double loop

- Operational single loop

- Operational double loop

- External factors

- Value added to customer

- Number of shared customers

In particular, the risk management factors are worth noting:

The first factor, measurement, refers to the mutual measurement of collaboration and the common striving for total cost reduction. The second factor, fault management, concerns joint quality and cost control, and the third factor is innovativeness, indicating the mutual development of new products and business areas and other innovations. Fourthly, prioritization of deliveries refers to delivery times, inventory control and contract management. The fifth risk management means include the protection of relationship-related knowledge and sixth, the amount of formal and informal communication.

What struck me though, was this

The suppliers stated that the most significant means were fault management and innovativeness, while reliability of deliveries and protection of knowledge appeared to be the least widely used.

I would argue that the least widely used are as important as the other.

Conclusion

As I stated in the very beginning, purchasing theory is not one of my particular strongholds, and I’ve never looked at it as a tool for researching and expressing supply chain risks, since the risks have been what has mattered to me. This paper however, is about to have me reconsider my attitude towards this strand of supply chain management, as I can see a clear link between transcations costs and risks and benefits in the supply chain. While perhaps not a direct reason for supply chain disruptions in transportation networks, which is what my own research is concerned with, I can see how supplier relationships, collaboration and organizational learning can make a difference in how organizations are able to handle actual disruptions, i.e. the potential for contingent and mitigative risk management.

Reference

HALLIKAS, J., PUUMALAINEN, K., VESTERINEN, T., & VIROLAINEN, V. (2005). Risk-based classification of supplier relationships Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 11 (2-3), 72-82 DOI: 10.1016/j.pursup.2005.10.005

Author links

- unknown: Jukka Hallikas

- linkedin.com: Kaisu Puumalainen

- unknown: Toni Vesterinen

- linkedin.com: Veli-Matti Virolainen

Related

- husdal.com: Friend or foe or both?