Maintaining a company’s competitive advantage depends on managing and controlling a global supply chain that is perhaps never static, and one major supply chain risk is that supply networks are constantly changing. Supply chains, once established, have become increasingly unpredictable in today’s global and highly dynamic business environment. No sooner have you mapped your supply chain end-to-end and devised a strategy for how to manage it, the chain changes on you – new and better suppliers emerge and new relationship configurations pop up. Perhaps not controlling, but letting things happen and letting supply networks emerge is the best management strategy? According to Supply networks and complex adaptive systems: control versus emergence by Thomas Choi, Kevin Dooley and Manus Rungtusanatham supply chain managers must appropriately balance how much to control and how much to let emerge.

Maintaining a company’s competitive advantage depends on managing and controlling a global supply chain that is perhaps never static, and one major supply chain risk is that supply networks are constantly changing. Supply chains, once established, have become increasingly unpredictable in today’s global and highly dynamic business environment. No sooner have you mapped your supply chain end-to-end and devised a strategy for how to manage it, the chain changes on you – new and better suppliers emerge and new relationship configurations pop up. Perhaps not controlling, but letting things happen and letting supply networks emerge is the best management strategy? According to Supply networks and complex adaptive systems: control versus emergence by Thomas Choi, Kevin Dooley and Manus Rungtusanatham supply chain managers must appropriately balance how much to control and how much to let emerge.

Complex adaptive systems

The term “complex adaptive system” refers to a system that emerges over time into a coherent form, and adapts and organizes itself without any singular entity deliberately managing or controlling it, similar to laissez-faire. It is perhaps also akin to what Ken Thompson refers to as a bioteam or swarm. That is quite the opposite of the traditional view of a supply chain as a static and deterministic system that can be planned, controlled and managed. However, viewing a supply network as a complex adaptive systems will facilitate more managerial options, and may even lead to better supply chain performance than a network that is subject to rigid control. How come?

Characteristics of complex adaptive systems

Complex adaptive systems are rooted in and take ideas from many sciences. The main focus of analysis is

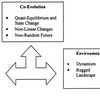

the interplay between a system and its environment and the co-evolution of both the system and the environment

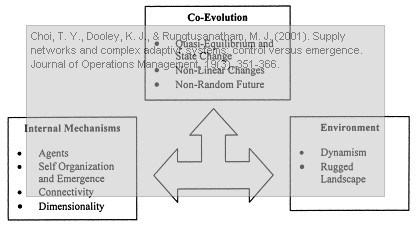

The dynamics of this interplay and co-evolution is described in the figure below:

When examining a complex adaptive system, three foci become evident: an internal mechanism, an environment, and co-evolution. These foci serve as the foundation the authors’ argument that a supply network is a complex adaptive system and it should be managed as such.

Internal Mechanisms

Internal mechanisms are the inner workings and underlying driving forces that bind or break a complex adaptive system.

Agents and schema

An agent may represent an individual, a project team, a division, or an entire organization. Agents have varying degrees of connectivity with other agents and possess schems, that is norms, values, beliefs, and assumptions that are shared among the collective.

Self-organization and emergence

Behavior in a complex adaptive system is not induced by a single entity but rather by the simultaneous and parallel actions of agents within the system itself. The behavior of each individual in the supply network, in the aggregate, may lead to complex behavioral pattern on a global scale.

Connectivity

Connectivity is what constrains the range options each individual entity has for itself, and in relation to the other entities. The more connected, the lesser the individual option, and the greater the collective force. The less connected, the weaker and more critical is the connection, but also vice versa, the tighter the coupling, the more critical it can become also, if the connection has a negative influence on performance.

Dimensionality

The dimensionality of a complex adaptive system is defined as the degrees of freedom that individual agents within the system have to enact autonomous behavior. The more autonomy an agent has, the more creativity emerges. Mind you, autonomous decision can be either constructive or destructive to the network as such.

Environment

The environment exists external to the complex adaptive system and consists of agents and their interconnections that are not part of the given system

Dynamism

A complex adaptive system can only thrive through in a constantly changing environment, because equilibrium and stasis means nothing less than death because the system depends on the exchange of interactions. Opening up the system boundaries, by excluding or including different agents and/or their partners and/or their networks and/or their connections changes the underlying pattern of actions and relations.

Rugged landscape

Because the environment is constantly changing as is the complex adaptive system itself, it is practically impossible to reach the optimum, it is only possible to reach a optimum. This local optimum can be an illusion, as one may sit on top of what appears to be a mountain peak, when, in fact, it may simply be a bunny hill. This uncertainty of what really is the optimum, coupled with a changing environment, creates the rugged landscape a complex adaptive system must work in.

Co-evolution

A complex adaptive system and its environment interact and create dynamic, emergent realities. The environment forces changes in the entities that reside within it, which in turn induce changes in the environment, or vice versa. This is what is meant by co-evolution.

Quasi-equilibrium and state change

Normally, a complex adaptive system is always in disequilibrium or in a quasi-equilibrium state or “point of chaos”, where it balances between complete order and incomplete disorder. This allows the system to maintain order while also enabling it to react to qualitative changes in the environment. However, if the internal system changes or external environmental changes push the system too far from this point, a subsequent change may lead to unpredicted and catastrophic changes, where equilibrium can no longer emerge.

Non-linear changes

Because behavior in a complex adaptive system stems from the complex interaction of many loosely coupled variables, the system behaves in a non-linear fashion. This also means that it will respond to changes in a non-linear manner, e.g. small changes generate large outcomes and large changes may generate only small outcomes. Essentially, the behavior of a complex system cannot be written down in closed form.

Non-random future

The inability to determine the future behavior of a complex system in an exact manner does not imply that the future is random, because complex systems, in fact, exhibit patterns of behavior that can be considered archetypal or prototypic. The exact future may not be able to be predicted, but directions or trends are possible.

Supply networks as complex adaptive systems

Building on their discussion, the authors then compare supply network to complex adaptive systems and find many similarities, leading them to ten propositions.

Agents and schema

1. The greater the level of shared schema (e.g. shared work norms and procedures, shared language) among allied firms in a SN, the higher will be level of fitness for each of these firms (e.g. firm performance).

Self-organization and emergence

2. Firms that adjust goals and infrastructure quickly, according to the changes in their customers, suppliers, and/or competitors, will survive longer in their SNs than firms that adhere to predetermined, static goals and infrastructure and are slow to change.

Connectivity

3. Within a SN, firms that are cognizant of activities across the supply chain (including the tertiary-level suppliers) will be more effective at managing materials flow and technological developments than firms that are cognizant of activities of only their immediate suppliers.

Dimensionality

4. Successful implementation of controloriented schemes (e.g. ERP, JIT II) leads to higher efficiencies, but it may also lead to negative consequences such as less than expected performance improvements and reduction in innovative activities by the suppliers.

5. The degree of innovation by suppliers is directly proportional to the amount of autonomy that suppliers receive in working with customers.

Dynamism

6. Supply networks that turn over quickly stand a better chance of exposing weak members and, thus, gaining higher efficiency than supply networks that are artificially bound by long-term relationships.

Rugged landscapes

7. Modularization of tasks will decrease overall inter-dependencies among firms in a supply network, and, thus, offer a higher efficiency when optimizing the overall system.

Quasi-equilibrium and state change

8. Over time, quantum changes will last longer within a supply network than incremental changes that go against the accepted practices.

Non-linear changes

9. Firms that deliberately manage their supply network by both control and emergence will outperform firms that try to manage their supply network by either control or emergence alone

Non-random future

10. In a supply network, upstream suppliers that are more diversified are more likely to survive than those that are not

Some of these make perfect sense, others need some pondering to sink in fully. Nonetheless it is obvious that supply network and complex adaptive systems have much in common. In the end, the authors come up with this definition:

A complex adaptive supply network is a collection of firms that seek to maximize their individual profit and livelihood by exchanging information, products, and services with one another. Therefore, the nature of interactions among firms adjacent in a supply network determines the type of behavior the network as a whole exhibits and the level of control that any one firm has over another.

The profit-maximizing nature of individual suppliers is perfectly described by Paul Cousins in my post on Biting the hand that feeds. “All firms are snakes” he says. Maybe they are? From a supply network management perspective, it is necessary to observe what emerges in or from the complex system and then make contingent, flexible and appropriate changes, while controlling the course of action toward the a priori determined goals.

Virtual enterprises?

Reading the above definition, it strikes that supply networks as complex adaptive systems have much in common with virtual enterprise networks. Interestingly, I did not mention the above article in the reference list of my book chapter on manging risk in virtual enterprise networks. At the time that I wrote it I probably hadn’t even read the article. Today the article makes perfect sense to me, and managing risks in supply networks is like managing risks in complex adaptive systems is like managing risks in virtual enterprise networks. That said, seeing supply networks as complex adaptive systems brings in a wider scope of disciplines outside of the virtual enterprise realm. Nonetheless, the linkage is clearly discernible.

Reference

Choi, T. Y., Dooley, K. J., & Rungtusanatham, M. J. (2001). Supply networks and complex adaptive systems: control versus emergence Journal of Operations Management, 19 (3), 351-366 DOI: 10.1016/S0272-6963(00)00068-1

Author links

- linkedin.com: Thomas Y Choi

- linkedin.com: M Rungtusanatham