What defines a crisis? Are there different types of crises? Crisis management is the focus of this week’s posts and today’s article attempts to develop a scheme for classifying different types of crises. In Towards a New Typology of Crises by Stephan Gundel, crises are classified according to how predictable and influenceable they are. This generates four types of crises: Conventional, Unexpected, Intractable and Fundamental crisis. Is that a useful differentiation for the practical handling of crises and for research into crisis management? Let’s look at how the author came to land on such a typology.

What defines a crisis? Are there different types of crises? Crisis management is the focus of this week’s posts and today’s article attempts to develop a scheme for classifying different types of crises. In Towards a New Typology of Crises by Stephan Gundel, crises are classified according to how predictable and influenceable they are. This generates four types of crises: Conventional, Unexpected, Intractable and Fundamental crisis. Is that a useful differentiation for the practical handling of crises and for research into crisis management? Let’s look at how the author came to land on such a typology.

Three basic questions

The paper seeks to answer three questions:

- Why do we need a typology of crises? What attributes characterize a crisis typology that is of use both today and in the future?

- What are the typologies used now and why are they not sufficient?

- What consequences for managing crises arise from a new typology of crises?

Why and how classifying crises?

Is it even useful to classify crises? The author admits that classifying crises is like shooting a moving target, because the events of the future are likely to be very different from today, and today’s unforeseen events, in hindsight, may no longer be seen as a crisis. That said,

Dealing with crises means dealing with crises is like dealing with nightmares, and nightmares become less of a threat if someone turns on the light. So classifying crises is the first step to keep them under control since they can be named and analyzed.

The first part of the paper of then describes the characteristics of a typology, which I will briefly reiterate, because I found it very useful:

- The classes in a typology should be mutually exclusive.

- The typology has to be exhaustive.

- The typology should be relevant and generate utility.

- The typology should be pragmatic, with manageable and ample heterogeneity between subsets.

Current crisis typologies

There are several basic typologies of different crises: man-made and natural crises, often popularized as “Acts of Men” and “Acts of God”. There are man-made, natural and social crises, there are normal and abnormal crises, there are avoidable and unavoidable crises or normal accidents, and while the paper discusses the various schools of thought and their champions, the term itself, what is “a crisis”, that is not discussed. A crisis definition would have been very helpful to the uninitiated reader. Nonetheless, the paper manages to convey that the classifications used to not conform with the above four criteria for typologies, and hence a new typology is needed.

Crisis classification criteria

Two features stand out when considering which proactive and reactive strategies to use in managing crises: Predictability and Influenceability. The former is always part of the public debate following a crisis event, because what everybody wants to know is “Why was this event/crisis not foreseen?”, similar to what Bazerman and Watkins wrote about predictable surprises. The signs were perhaps there, in plain sight for those who cared to look, and the other day I wrote about how crises develop into crises because of organizational imperfections and managerial ignorance. Even if the signs were not there, there’s always the public question of “Why was this crisis/event not handled in a better way?” The latter is thus crucial in establishing effective contingency measures, and avert any reputation risk. Can we predict a crisis? and Can we influence a crisis? are thus two excellent measures for defining crises:

A crisis is predictable, if place, time or in particular the manner of its occurrence are knowable to at least one third competent party and if the probability of occurrence can not be neglected.

A crisis can be influenced if responses to stem the tide or to reduce damages by antagonizing the causes of a crisis are known and possible to execute.

While I perhaps would have chosen different words for the definitions, the meaning is clear. Some crises can be predicted, soem not, some can be influenced, some not.

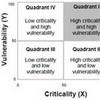

Crisis matrix

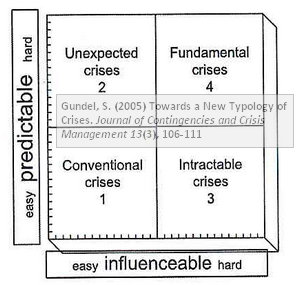

With the predictability and influenceability of crises as two axes along which crises can be classified, a crisis matrix can be constructed as follows:

Conventional crises are located in the first quadrant, they are predictable and influenceable. Typical examples are technological events are Bhopal disaster and the Estonia ferry sinking. Unexpected crises are found in the second quadrant, they hard to predict, but can be influenced when they occur. Typical examples here are the Kaprun tunnel blaze and the Mann Gulch fire disaster. Intractable crises can be anticipated but interference is practically impossible, making responding difficult and preparing hard. Typical examples are the Heysel Stadium disaster and Chernobyl nuclear power plan accident. Fundamental crises are located in the fourth quadrant and and represent the most dangerous class of crises, since they can be neither predicted nor influenced. As a typical example the author cites the 9/11 terrorist attack, although I believe that some critics will probably say that this should have been seen and and should have been averted.

Conclusion

I agree with the author in that this framework is useful in both classifying and in managing crises. It is elastic and not static, because it allows for the placement of crises to be adjusted over time, as experience with crises and better modelling and prediction techniques will allow for future crises to be seen ahead of time and to be handled more appropriately than those of the past.

Reference

Gundel, S. (2005). Towards a New Typology of Crises Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 13 (3), 106-115 DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2005.00465.x

Author link

- ssi-schweiz.ch: Stephan Gundel

Related

- Stephan Gundel, Lars Mülli: Unternehmenssicherheit