I’m a quantitative researcher, so I usually shy away from journal articles with too many equations and complicated calculations. This one, however, I can not avoid mentioning, because it is brilliantly simple, despite its seemingly complicated looks. In their article, aptly titled Mitigating Supply Chain Vulnerability, Brian D Neureuther and George Kenyon develop a risk assessment index that can be used to measure the vulnerability of different supply chain structures. While it is apparently straightforward to calculate this risk index, it is subject to a number of assumptions that are not equally straightforward to quantify. Is it still worth reading and using?

I’m a quantitative researcher, so I usually shy away from journal articles with too many equations and complicated calculations. This one, however, I can not avoid mentioning, because it is brilliantly simple, despite its seemingly complicated looks. In their article, aptly titled Mitigating Supply Chain Vulnerability, Brian D Neureuther and George Kenyon develop a risk assessment index that can be used to measure the vulnerability of different supply chain structures. While it is apparently straightforward to calculate this risk index, it is subject to a number of assumptions that are not equally straightforward to quantify. Is it still worth reading and using?

Risk, reliability, costs and efficiency

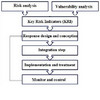

In the article, the authors test the vulnerability of three typical supply chain structures:

- single source

- multiple source

- multiple single source

using these four parameters:

- structural reliability

- consequence score

- organizational costs

- process efficiency

- risk index

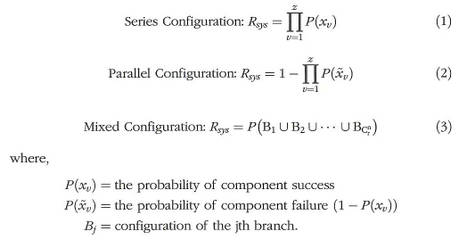

The structural reliability parameter follows the traditional reliability setup:

Finding these probabilities, though, is not an easy task in a supply chain with potentially tens, if not hundreds of suppliers.

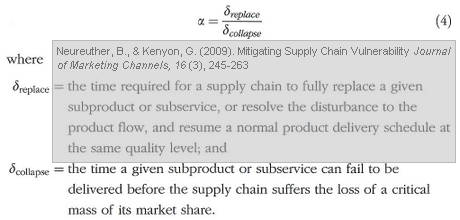

The consequence score establishes the parameter for evaluating the impact of a supply chain disruption:

The range of the consequence score is between 0 and 1 , because if δreplace is larger than δcollapse, the supply chain ceases to exist, and the authors suggest the following categorization for evaluating the consequences:

| α | Importance | Substitute? |

| 1.0 | Vital | Not replaceable |

| 0.6 | Necessary | Not easily replaced |

| 0.3 | Necessary | Easily replaced |

| 0.1 | Desired | Easily replaced |

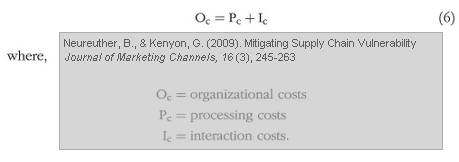

The organizational costs are straightforward economic terms:

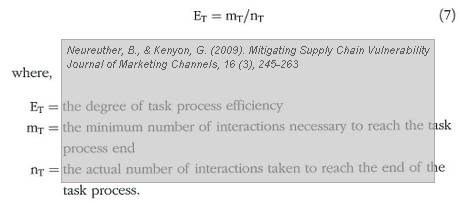

The process efficiency is simply a ratio of interactions:

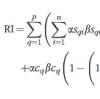

Finally the risk index, perhaps the most intricate equation, with the most unknowns that are presumed known:

Before calculating these parameters, the following assumptions must be considered:

Each subproduct group is providing the same amount of support to the supply chain.

All suppliers with a subproduct group are independent and non-identical.

All customers are independent and non-identical. All suppliers within a subproduct group are providing the same amount of support to the supply chain.

Processing costs for an interaction is equal to one unit of cost for each firm and structure.

There is no reliability growth.

How often does this hold true in a real supply chain?

Anyway, after running through a scenario of 10 different supply chain configurations the authors discover (not all surprising) that

There is a significant reduction of risk associated with having more than one supplier per subproduct or service.

Adding subproduct diversification does not affect risk, but improves the structural reliability of the supply chain.

The structural reliability of the supply chain increases when the number of suppliers providing the same subproduct or subservice increases.

Coordination costs decrease when the number when the number of suppliers providing subproducts or subservices decreases.

Coordination efficiency increases when the number when the number of suppliers providing subproducts or subservices decreases.

Essentially, the results indicate that excessive diversification is counterproductive, and that there are indeed limitations as to what can be gained from outsourcing.

Critique

What I enjoy most about the approach these authors use, is how they combine several separate fields of research, i.e. reliability, economics, and operations, into seven equations that make four parameters. I wish I had come up with something similar in my previous attempts at establishing a measure of reliability and vulnerability in transportation networks. In a way they are only echoing what Smith and Buddress wrote in 2005, who said that

Supply Chain Management needs a new way to pursue research, a new way that is focused on theory building based on learned borrowing from other disciplines.

As James Stock wrote in 1997, Broader research makes better research, something Neureuther and Kuhn prove to the full. That said, the model hinges on a lot of assumptions, let alone probabilities, which have to be established or guesstimated first. That done, this model is – in my humble opinion – an excellent tool for exploring supply chain vulnerability.

Reference

Neureuther, B., & Kenyon, G. (2009). Mitigating Supply Chain Vulnerability Journal of Marketing Channels, 16 (3), 245-263 DOI: 10.1080/10466690902934532

Author links

- linkedin: Brian D Neureuther

- lamar.edu: George Kenyon

Related

- husdal.com: Reliability and vulnerability, a matter of cost and benefit?

- husdal.com: Broader research = better research?

- husdal.com: SCM – the new research cocktail?