Supply chains are increasingly becoming complex webs and networks and are no longer straightforward chains with just a few links between supplier and customer. Supply chains have indeed become complex systems, and the system thinking that pervades Einarsson and Rausand (1997) An Approach to Vulnerability Analysis of Complex Industrial Systems is perhaps applicable to supply chains? Why? Perhaps because, really, there is little difference between vulnerability in supply chains and vulnerability in complex industrial systems.

Supply chains are increasingly becoming complex webs and networks and are no longer straightforward chains with just a few links between supplier and customer. Supply chains have indeed become complex systems, and the system thinking that pervades Einarsson and Rausand (1997) An Approach to Vulnerability Analysis of Complex Industrial Systems is perhaps applicable to supply chains? Why? Perhaps because, really, there is little difference between vulnerability in supply chains and vulnerability in complex industrial systems.

An old acquaintance

In a previous post on his blog I reviewed a 1997 Norwegian research report written by Bjørn Asbjørnslett and Marvin Rausand that discussed the vulnerability of production systems. The ideas from the report were in 2008 incorporated into a book chapter, written by Bjørn Asbjørnslett, titled Assessing the Vulnerability of Supply Chains and published in Supply Chain Risk, edited by George Zsidisin and Bob Ritchie. However, as it turns out, the same ideas were already journal published in 1997, and that is the article I am highlighting today.

What is vulnerability?

The authors define vulnerability as related to

any property of an industrial system (its premises, facilities and production equipment, including its human resources, human organization and all its software, hardware and net-ware) that may weaken or limit its ability to endure threats and survive accidental events that originate both within and outside the system boundaries.

Vulnerability, they say, is thus the opposite of robustness and resilience. Robustness is static damage tolerance, while resilience is dynamic adaptation to changing circumstances. For the inquisitive reader, I have elaborated on this distinction in my post that discusses robustness, resilience, flexibility and agility.

Cause and effect

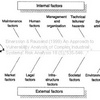

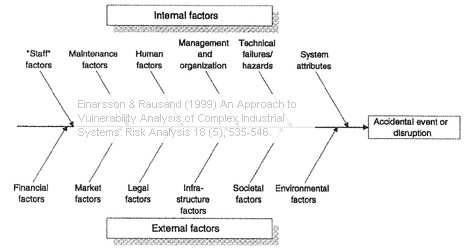

The article makes an attempt at listing all potential threats, internal or external, that may (or may not) lead to an accidental event or disruption, and give reasons for why they should be included. The list is not exhaustive, but it does highlight some of the important issues.

Internal Risk Factors

System attributes: Some systems are so complex that accidents are bound to happen, for two reasons: system interaction (linear or complex) and system couplings (loose or tight).

Technical Failures and Technical Hazards: The reliability of the technical equipment and components has a significant influence on a system’s vulnerability.

Human and Organizational Factors: Human factors are often considered to be the main potential for improving the safety performance in most organizations.

Maintenance Factors: Interestingly, many major accidents seem to occur during maintenance or because of inadequate or wrongly executed maintenance.

Staff Factors: This comprises strikes and labor conflicts, loss of key personnel, recruitment of skilled personnel, safety culture, unfaithful servants, liability claims (hazardous work environment), to name but a few. The personnel itself, along with the organizational factors are key ingredients in a company’s vulnerability.

External Factors

Environmental Factors: The vulnerability of a company may depend on a wide range of environmental – or natural- hazards that are specific and unique to a given location.

Societal Factors: The vulnerability of a system can be linked to a range of societal and political factors leading up to an accidental event, e.g. political unrest or unforeseen price hike for spare parts leading to lesser maintenance in fear of cost overrun. The full consequences, too, may depend on the societal and political situation in which an event occurs, if the circumstances are detriment to proper crisis management procedures.

Infrastructure Factors: Many companies are extremely vulnerable to disruptions in one or many of these infrastructures: transportation, telecommunication, electric power, water supply, sewage, and whatever else the company relies on. This also includes illegal penetration of premises or computer networks.

Legal and Regulatory Factors: A company may be subject to sudden new laws and regulations, particularly following an accident or serious near accidents, or often as a result of changing political and societal factors.

Market Factors: The market has both political and social dimensions, where products or services may become obsolete or outperformed by competitors, or perhaps reputably damaged following an accident. Raw materials may become scarce or unaffordably costly.

Financial Factors: Economic decisions that go wrong (as in close to bankruptcy) are not a threat per se, but may lead to a feeling of uncertainty, which in turn becomes a breeding ground for other potential threats.

Admittedly, not exhaustive perhaps, but I find it fair to say that this list is not very unlike the list of risks found in Manuj and Mentzer (2008) Global Supply Chain Risk Management, proving that complex industrial systems and supply chains have much common ground.

Disruption effects

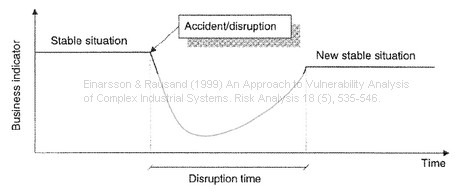

An accidental event produces a consequence scenario, a disruption that tests the systems survivability, illustrated by the figure below, a figure that is among other places, found in Sheffi’s Resilient Enterprise.

How long does it take for the company to reach the new stable situation? Setting a target for this should be at the heart of any business recovery plan, because obviously, the longer the disruption time, the greater the vulnerability, and the lesser the robustness and resilience.

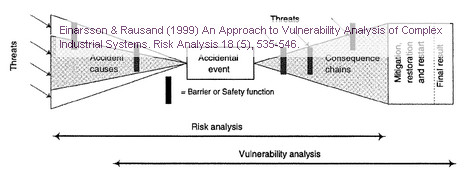

Vulnerability versus Risk

It is important to separate risk analysis from vulnerability analysis. A risk analysis is mainly limited to accidental events taking place within the immediate physical boundaries of the system. The main focus is the possible event chains following an accident. A risk analysis may include the barriers needed to mitigate, i.e. prevent accidents, but the actions needed to restore and restart the system are usually nor part of the traditional risk analysis. They belong to the vulnerability analysis, which focuses on the whole disruption period until a new stable situation is reached.

The barrier concept must therefore be broader than for risk analysis. Thus the objectives of a vulnerability analysis of an industrial system seek to

Identify potential threats to the system

Verify that the vulnerability of the system is acceptable

Verify that the system has adequate security and safety

Evaluate the cost-effectiveness of proposed actions

Aid in establishing an emergency preparedness plan

Help design a robust or resilient system

The focal point of a vulnerability analysis is the survivability of the system.

Vulnerability Analysis

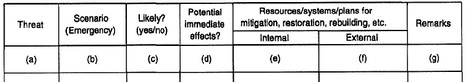

The authors suggest a two-step worksheet approach towards a vulnerability analysis. The overall objective of the first step is to increase the awareness of potential disturbances or accidents that may threaten the survivability of the system, what the immediate impacts and scenarios are and whether (or not) there already exist resources for dealing with these threats.

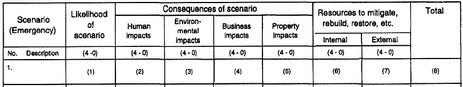

The objective of the second step is a quantitative assessment of the scenarios in the first step, and to establish a ranking according to their criticality. Here the authors suggest a 0-4 weighting for the parameters: Likelihood (very unlikely, unlikely, likely, very likely), Consequences (Human, Environmental, Business, Property; negligible, some impact, much impact, critical impact), Resources (Internal, External; not available, available but not adequate, available but not fully adequate, available and fully adequate).

Each scenario can now be ranked according to the weighted sum of likelihood, consequences and resources. Disruption is not part of the worksheet per se, but can easily be included as a parameter as well.

Conclusion

In hindsight, the article was written some 12 years ago, but it still holds true, and it has not become less important. Much of the above have found its way into the risk and vulnerability literature of today, and is well known to today’s risk researchers and risk professionals. I myself have used a similar approach in analyzing the vulnerability of transportation networks.

Besides, a good topic cannot be repeated to often, can it?

It has been claimed that only a massive emergency can verify the ultimate efficiency of a company’s emergency preparedness. That may be true, but it is no excuse for not being prepared.

So say Einarsson and Rausand. Many companies are (un)fortunately blissfully unaware of their vulnerability, and a risk and vulnerability analysis is a small step towards better preparedness. This article shows how it can, and perhaps also, how it should be done.

Reference

Einarsson, S., & Rausand, M. (1998). An Approach to Vulnerability Analysis of Complex Industrial Systems Risk Analysis, 18 (5), 535-546 DOI: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb00367.x

Author links

- linkedin.com: Marvin Rausand

- unknown: Stefán Einarsson

Related

- husdal.com: Vulnerability of Production Systems

- husdal.com: Book Review: Supply Chain Risk