The German automotive industry. Volkswagen, Mercedes, Porsche, Audi, BMW. The embodiment of craftsmanship, functionality and reliability. Cars that work and an industry that knows how to make it work. But how about supply chain risk management? Does that work equally well? That is what Jörn-Henrik Thun and Daniel Hoenig set out to investigate in daptive Fit Versus Robust Transformation: How Organizations Respond to Environmental Change. Interestingly, the results show that the group using reactive supply chain risk management seems to do better in terms of disruptions resilience or the reduction of the bullwhip effect, whereas the group pursuing preventive supply chain risk management seems to do better as to flexibility or safety stocks.

The German automotive industry. Volkswagen, Mercedes, Porsche, Audi, BMW. The embodiment of craftsmanship, functionality and reliability. Cars that work and an industry that knows how to make it work. But how about supply chain risk management? Does that work equally well? That is what Jörn-Henrik Thun and Daniel Hoenig set out to investigate in daptive Fit Versus Robust Transformation: How Organizations Respond to Environmental Change. Interestingly, the results show that the group using reactive supply chain risk management seems to do better in terms of disruptions resilience or the reduction of the bullwhip effect, whereas the group pursuing preventive supply chain risk management seems to do better as to flexibility or safety stocks.

Vulnerability of supply chains

From the fact that many companies engage in supply chain risk management practices, presumably because it is needed, the authors formulate their first hypothesis:

Supply chains are regarded as being susceptible to supply chain risks. (H1)

Drivers of supply chain risks

The authors list a number of drivers or trends that contribute to increasing supply chain risks. Essentially, this list reads like a copy of what Martin Christopher wrote in his chapter on supply chain risk in his book, Logistics and Supply Chain Management:

- Focus on efficiency instead of security aspects

- Globalization of the supply chain

- Focus on central distribution

- Enforced outsourcing

- Reduction of suppliers

- Increased product variety

- Centralized production

From this the authors postulate the following hypothesis:

Complexity and efficiency are key drivers for supply chain risks. (H2)

Supply Chain Risks

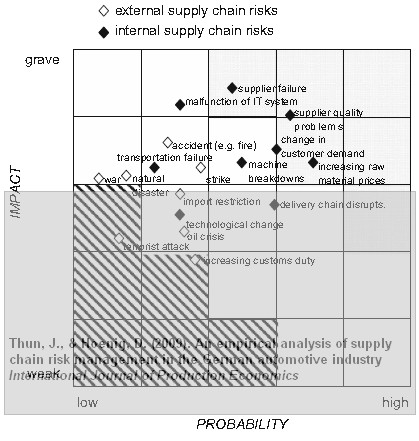

The list of potential risks and their impacts reads almost like the list I presented yesterday from a study on supply chain and logistics risks in Germany:

- Supplier failure

- Supplier quality failure

- Oil crisis

- Terrorist attack

- Strike

- Malfunction of IT-systems

- Accident

- Natural disaster

- Machine breakdown

- Import or export restrictions

- Transportation failure

- Delivery chain disruption

- Increasing customs duty

- Change in customer demand

- Technological change

- Increasing raw material prices

Because these risks exist external or internal to the supply chain, the next two hypotheses are formulated as such, while at the same time appreciating the probability and impact of risk events:

Internal supply chain risks have a higher likelihood to occur than external supply chain risks. (H3a)

External supply chain risks have a greater impact on the supply chain than internal supply chain risks (H3b)

Instruments of supply chain risk management

The authors differentiate supply chain risk management (SCRM) instruments as being either reactive or preventive. This is similar to my own formulation of mitigation versus contingency in risk management strategies, and leads to the final two hypotheses:

Companies with a high degree of supply chain risk management show a higher performance than companies with a low degree of supply chain risk management. (H4a)

There is a difference in terms of performance criteria between companies using preventive instruments contrary to those using reactive instruments. (H4b)

Hypothesis testing

Based on a survey designed to confirm or reject the above hypotheses, the authors conclude that only H3b is to rejected, i.e. that external supply chain risks do not have a greater impact than internal supply chain risks.

Supply chain risks – probability and impact

The probability/impact matrix of supply chain risks in the German automotive industry looks like this:

Although not directly comparable to the probability-impact-matrix developed by Pfohl et al. (2008), which I presented yesterday, similar trends can be discerned.

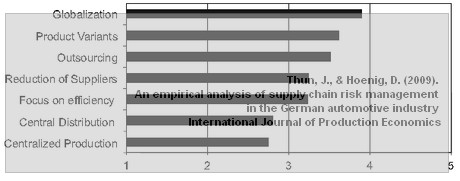

Globalization – risk number one

When asked about which driver of supply chain risk that is most important, these are the answers on a 1-5 Likert scale:

While globalization topping the list is no surprise, it is more confounding to see product variety listed as a risk factor.

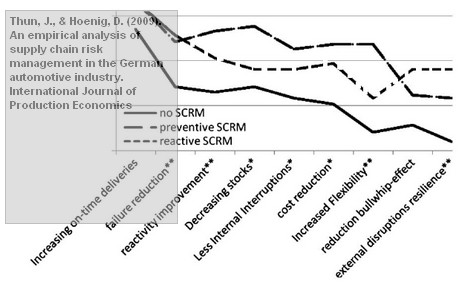

Reactive versus preventive supply chain risk management

When comparing the supply chain performance of companies using preventive versus reactive risk management (mitigation versus contingency strategies), an interesting picture emerges:

Obviously, with no or little SCRM in place, the overall supply chain performance is rather lackluster. In general, preventive SCRM seems to fare better than reactive SCRM, but reactive SCRM does better when faced with reacting to external risks, as well as the bullwhip effect. Preventive SCRM is particularly useful in decreasing stocks and inventory. It also appears that a resilient supply chain cannot – at the same time – be a flexible supply chain.

Critique

This is an excellent study that highlights the virtues of preventive versus reactive supply chain risk management. I do question the selection of supply chain risk drivers, though, and in particular the “ambiguity” that is inherent in “globalization”. Maybe I’m just playing the devil’s advocate, but what exactly is meant here? Globalization is a very vague term in my opinion. Another question is the juxtaposition of efficiency and security. Others may disagree, but I do not necessarily see a conflict here. Nonetheless, the study is worthwhile pondering, and it would be very interesting to see if the same conclusions about risk drivers and supply chain performance also apply to businesses not in the automotive industry. For now, what I can say, is that German autos are not at risk.

Reference

Thun, J., & Hoenig, D. (2009). An empirical analysis of supply chain risk management in the German automotive industry International Journal of Production Economics, 131 (1), 242-249. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.10.010

Author links

- researchgate.net: Jörn-Henrik Thun

- tum.de: Daniel Hoenig

Second opinion

For a second opinion on this article you may want to check out what Daniel Stengel had to say on the SCRMBlog:

External risks in this sample of companies has been perceived as not more impactful than internal risks. So this might be true or it might be based on a skewed perception. What do you think? And if it’s true, does this hold true for all industries?

I don’t know, Daniel, but I think you raised some issues I may have overlooked.