Maritime transport is a vital backbone of today’s global and complex supply chains. Unfortunately, the specific vulnerability of maritime supply chains has not been widely researched. This paper by Øyvind Berle, Bjørn Egil Asbjørnslett and James B Rice puts it right and presents a Formal Vulnerability Assessment of a maritime transportation system. This is not the first maritime paper that Asbjørnslett has contributed to on this blog, and he keeps up the good work he started in 2007, when he presented Coping with risk in maritime logistics at ESREL 2007.

Maritime transport is a vital backbone of today’s global and complex supply chains. Unfortunately, the specific vulnerability of maritime supply chains has not been widely researched. This paper by Øyvind Berle, Bjørn Egil Asbjørnslett and James B Rice puts it right and presents a Formal Vulnerability Assessment of a maritime transportation system. This is not the first maritime paper that Asbjørnslett has contributed to on this blog, and he keeps up the good work he started in 2007, when he presented Coping with risk in maritime logistics at ESREL 2007.

Maritime transport – a forgotten part of supply chains?

I guess it is true that maritime transport or sea transport is an overlooked part of supply chains, even on this blog. In my more than 500 posts the word “maritime only occurs in 20 of them. Well, perhaps not so forgotten, but maybe such an obvious part of today’s supply chains that it is not looked at specifically, and just assumed to be part of the wider picture. Considering Norway’s maritime and seafaring tradition, it is not surprising to see Norwegian researchers taking up this particular question. One of the authors, Asbjørnslett, is part of the Marine System Design research group at the Department of Marine Technology at NTNU in Trondheim, Norway, where he among other topics is involved in research related to risk taxonomies in maritime transport systems, risk assessment in fleet scheduling, and studies of vessel accident data for improved maritime risk assessment.

The invisble risk?

It is interesting to see what starting point the authors use in their introduction, namely the 2008 Global Risk Report by the World Economic Forum. In my post on Supply Chain Vulnerability – the invisible global risk I highlighted that report, which listed the hyper-optimization of supply chains as one of four emerging threats at that time, and as the authors put it:

[…] risks in long and complex supply chains are obscured by the sheer degree of coupling and interaction between sources, stakeholders and processes within and outside of the system; disruptions are inevitable, management and preparation are therefore difficult […]

Akin to the infamous “Butterfly effect”, even a minor local disruption in my supply chain could have major and global implications not just on the company directly linked to the supply chain, i.e. me, but also on other businesses. Or conversely, some other company’s disruption may affect me severely, even though I in no (business) way am connected to said company.

Issues and questions

With that in mind the authors set out to address these particular issues they found in their preliminary observations:

I1—respondents have an operational focus; in this, they spend their efforts on frequent minor disruptions rather than the larger accidental events.

I2—stakeholders do know that larger events do happen, and they know that these are very costly, yet they do not prepare systematically to restore the system.

I3—maritime transportation stakeholders find their systems unique. As a consequence, they consider that little may be learnt from benchmarking other maritime transportation system’s efforts in improving vulnerability reduction efforts.

I4—there seems to be little visibility throughout the maritime transportation system.

which led them to to propose these research questions:

RQ1—what would be a suitable framework for addressing maritime transportation system vulnerability to disruption risks?

RQ2—which tools and methods are needed for increasing the ability of operators and dependents of maritime transportation to understand disruption risks, to withstand such risk, and to prepare to restore the functionality of the transportation system after a disruption has occurred?

I like this introduction, clearly identifying a direction and purpose of the paper.

FSA – Formal Safety Assessmement

In order to solve the research questions the authors transfer the safety-oriented Formal Safety Assessment (FSA) framework into the domain of maritime supply chain vulnerability, and call it Formal Vulnerability Assessment (FVA) methodology. FSA – for those of you who don’t know, including me – is a structured and systematic methodology, aimed at enhancing maritime safety, including protection of life, health, the marine environment and property, by using risk analysis and cost benefit assessment:

What might go wrong?

= identification of hazards (a list of all relevant accident scenarios with potential causes and outcomes)

How bad and how likely?

= assessment of risks (evaluation of risk factors);

Can matters be improved?

= risk control options (devising regulatory measures to control and reduce the identified risks)

What would it cost and how much better would it be?

= cost benefit assessment (determining cost effectiveness of each risk control option);

What actions should be taken?

= recommendations for decision-making (information about the hazards, their associated risks and the cost effectiveness of alternative risk control options is provided).

While not fully the same, this assessment follows in essence the ISO 31000 risk management steps of risk identification, risk analysis, risk evaluation and risk treatment, a framework that I am very familiar with.

Deconstructing the maritime transport network

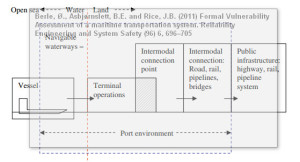

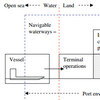

What I like in particular is how they deconstructed the maritime transport network, divided the land from the sea and looked at how a vessel interacts with a port that in turn interacts with other modes of transport:

It’s a figure that reminds of my last project I took part in during the autumn of 2011 while still in academia, where we investigated Customer and Agent Initiated Intermodal Transport Chains, and looked at barriers and incentives to competition and collaboration in intermodal transport. I’m not sure the figure would have helped if I had known about it, but it would have made a few things a bit clearer. Kudos to Berle et al. for coming up with it.

Kaplan and Garrick

It is rare to find papers like this that use Kaplan and Garrick’s definition of risk:

Risk may be defined as a triplet of scenario, frequency and consequence of events that may contribute negatively (in this case to the transportation system’s ability to perform its mission. A hazard is a source of potential damage; Kaplan and Garrick describe risk as hazards divided by safeguards. In this, risks cannot be completely removed, only reduced.

I do like this definition of risk, because risk can be seen as incompletely described unless all three elements are in place. An untrained individual or business entity often stops short after the first, or maybe the second question, without fully considering the third. In risk management, addressing the impacts is an important issue, which is why the consequences need to be considered along with the likelihood and source of risk. In this paper, developing a method for assessing the vulnerability i.e. consequences, and deconstructing the maritime transport network, i.e. scenario, this definition of risk makes a lot more sense than any other definition of risk.

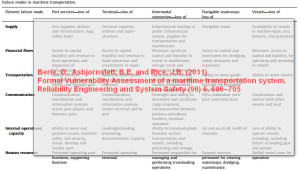

Failure modes

Another interesting idea in the paper is the concept of failure modes, taken from the book System Reliability Theory: Models, Statistical Methods, and Applications, written by two Norwegian professors (from NTNU, again, no surprise). Failure modes are used to investigate and understand how the maritime transport system is able to handle unexpected hazards and threats and low-frequency high impact scenarios:

Failure modes are defined as the key functions and capabilities of the supply chain, loss of any such would reduce or remove the ability of the system to perform its mission.

The concept of “mission” is important here, because it emphasizes what vulnerability in a systems perspective is, namely the inability to function and deliver (whatever the system is supposed to deliver):

The critical ways a transportation system may fail can be summed up as the loss of capacity to supply, financial flows, transportation, communication, internal operations/capacity and human resources, which may be described as follows: supply capacity is the ability necessary to source provisions needed for the element to perform its function; for a factory, this is inbound materials, utilities and electricity. Financial flows cover the ability to access capital and liquidity/cash flow. Transportation is the ability to move materials, including those presently at work. Communication would include enabling technology, and is vital for transparency in the supply chain. Internal operations entail the organization’s processing capacity (e.g. converting materials into a good). Quality issues reducing outputs fall into internal operations. Loss of human resources singles out the human factor explicitly from internal operations—what are the personnel needs for the supply chain functions?

The concept of failure modes is an idea the authors developed in a previous paper, Failure modes in ports – a functional approach to throughput vulnerability, a paper which I will review as soon as I get a copy of it. I think the failure modes concept captures the idea of what could go wrong in the maritime supply chain, as seen from a systems perspective:

Hazards and Mission

This is where it gets interesting. In order to transfers the FSA into a FVA, the FVA hazard focus is shifted towards the FVA mission focus. For example, the question of what can go wrong is turned into the question of which functions/capabilities should be protected (to ensure the functionality of the maritime transport system). The same is done for the other questions. Where the FSA looks at measures to mitigate most important risks the FVA looks at measures to restore functions/capabilities. This kind of parallel or similar thinking shows how easy it may be to transfer a concept from one domain into another domain.

Case example – LNG

The FVA is put to test in practice, using LNG (Liquid Natural Gas) shipping as their case. At first I thought there must be better examples, but the issue is that

[…] this analysis is relevant to study energy import dependencies, as current LNG supply chains are optimized to the level that much of the system storage and flexibility can be found in the shipping element, lacking on-shore infrastructure […]

and therefore, definitely a case worth studying.

Conclusion

Not only do the authors develop a conceptual framework for assessing the vulnerability of maritime transport networks, the successfully transfer the maritime Formal Safety Assessment (FSA) framework into the domain of maritime supply chain vulnerability and demonstrate that the approach works. It is not done according to IMO’s own standard, the FSA, thus extending vessel safety to port safety and supply chain safety. I think that this will help this approach gaining acceptance within the wider maritime community. The paper is well-written and well-structured, but I could have wished for a bit more about the FSA. Never having heard about it I had to do some research to find what this was all about. All in all, the paper is a showcase example of how easy it can be to transfer concepts from one domain to another domain, exemplifying a cross-fertilization of research strands.

Reference

Berle, Ø., Asbjørnslett, B.E. and Rice, J.B. (2011) Formal Vulnerability Assessment of a maritime transportation system. Reliability Engineering and System Safety (96) 6, 696–705 DOI: 10.1016/j.ress.2010.12.011

Author links

- linkedin.com: Bjørn Egil Asbjørnslett

- linkedin.com: James B. Rice

- linkedin.com: Øyvind Berle

Read online

Related links

- imo.org: Formal safety assessment

Related posts

- husdal.com: Risk and resilience in maritime logistics

- husdal.com: Security in maritime supply chains