Supply chain disturbances and supply chain disruptions. Not the same and very different from each other. The former can be managed and solved within an established supply chain, the latter often requires establishing a new supply network. That is why Phil Greening and Christine Rutherford assume a network perspective in their recent article titled Disruptions and supply networks: a multi-level, multi-theoretical relational perspective. Here they develop a conceptual framework for the analysis of supply network disruptions and present a number of propositions to define a future research agenda. The ability to understand the implications of network structure and network relational dynamics in the context of disruption will enable managers to respond appropriately to disruptive supply chain events, so they say.

Supply chain disturbances and supply chain disruptions. Not the same and very different from each other. The former can be managed and solved within an established supply chain, the latter often requires establishing a new supply network. That is why Phil Greening and Christine Rutherford assume a network perspective in their recent article titled Disruptions and supply networks: a multi-level, multi-theoretical relational perspective. Here they develop a conceptual framework for the analysis of supply network disruptions and present a number of propositions to define a future research agenda. The ability to understand the implications of network structure and network relational dynamics in the context of disruption will enable managers to respond appropriately to disruptive supply chain events, so they say.

Chain versus network

A supply chain is actually a misnomer. While this may be true in some case, more often than not it is a network, not a chain, as can be seen in Harland et al. (2003) and their article on Risk in supply networks. This misconception of the supply chain as a chain has also resulted in another erroneous image of what a supply chain is, namely the buyer-supplier dyad or buyer-supplier relationships, as seen in Triads in supply networks by Choi and Wu (2009).

The usual conceptualization of a supply chain as a chain has resulted in them being described from a focal firm perspective, neglecting the interdependencies between supply chains (e.g. shared suppliers). The overlapping nature of supply chains is more accurately described by a network. This location of supply chains as an element of a supply network is important in the consideration of events that have impact beyond a single supply chain.

Consequently, it is only when viewing the supply chain as a supply network that the full consequences of a disruption emerge, and thus, we need to separate the wheat from the chaff or the network from the chain:

- a supply chain describes the flow of information, materials and cash into and out of a focal company; and

- a supply network describes the connections between supply chains that share common elements.

Essentially then, while the focal firm has a supply chain, this chain at the same time is part of a larger network, as seen in Jüttner et al. (2003) an their Supply Chain Risk Management – Outlining a Future Research Agenda.

Disturbances versus disruptions

If we separate the chain form the network, then, when looking at the whole system, it is possible to discern between disturbances (affecting one focal company or one chain) and disruptions (affecting many companies and the entire network or parts of it), much like Peck (2006) did in Reconciling supply chain vulnerability, risk and supply chain management.

Disturbances can be separated from disruptions in terms of their impact on a supply network. Disturbances involve connected supply chain actors adapting to variations in material flow or information. This process of adaptation is constrained by the structure of the chain, that is to say that the chain structure does not change as a result of the adaptation process.

Disruptions involve the removal of ties/nodes from the network (either permanently or temporarily) as a consequence of some unanticipated critical event. As a result, the post-disruption network structure is irreversibly different to the pre-disruption network and the adaptation process inevitably involves the residual actors renegotiating existing and in some cases establishing new relationships, resulting in an irreversible change to the network structure.

In summary, disruptions differ from disturbances in terms of their range and impact. Disturbances do not change the chain structure whilst disruptions result in network irreversible structural changes. Network responses to disruption differ from normal network formation and evolution processes, in that the latter involves a considered process not constrained by time, whilst the former requires an urgent adaptation constrained by time.

This concept is not so unlike the deviation-disruption-disaster framework used in the book chapter on Risk Management in Global Supply Chain Networks by Visanadham and Gaonkar (2008), whose disruptions are the same as disturbances and whose disasters are the same as disruptions. Interestingly, this almost the same concept is not mentioned in the reference list for this article, but considering the search methodology they used in their literature review, it is not surprising that they did not find it.

Literature review explained

Regular readers will remember my previous post on a literature review article that explored how supply chain risk management research had evolved over the past decade, where I lamented that the researchers did not disclose much about their search methodology, thus making it difficult to follow their steps. Not so in this article. Here the authors provide detailed step-by-step information on how they searched, e.g. citation/co-citation is thoroughly explained, and also what particular keywords they used. This is indeed very helpful for other researchers attempting similar types of reviews in other fields of research. In this case, the following keywords were used and linked with supply chain disruption or supply chain disturbance: transaction cost economics (TCE, resource dependency, resource based (theory or view), buyer seller relationships, economic organization, network formation, social networks. Had I been on the team I probably would have included supply chain turbulence and supply chain volatility, and maybe more, just to make sure I get as many articles as possible.

Networks and relationships

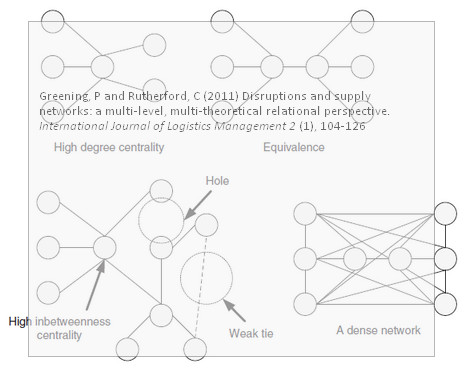

Particular emphasis was put on articles relating to relationship formation, relationship dynamics, network formation, network attributes, and why firms form networks and relationships, leading to different-looking types of networks:

The authors postulate that

each of these network attributes has a particular significance in the way that networks respond to disruption. For instance, a disruption occurring at a node with high inbetweenness centrality will result in a greater disconnection amongst the network actors than a disruption occurring in a node with low inbetweenness centrality. In a similar fashion network, holes represent opportunities for nodes to build new connections with previously unconnected nodes following a disruptive event. Nodes with high-degree centrality enjoy a privileged position of power, which they may or may not use to their advantage, and this is in contrast with the network attribute of equivalence, which describes nodes, with no comparative privilege. The role of weak ties in responses to disruption may be of particular significance, as they are recognized as a mechanism for the effective dissemination of information across a network. If part of a network becomes aware of a disruption sooner than another part of the network, it follows that its actions are likely to be more effective in mitigating the impact of disruption.

Well spoken and perhaps not so unlike Cheng and Kam (2008) and their view of how disruptions propagate through a network and impact just a link or a node, a subnetwork, or – worst case – the entire network.

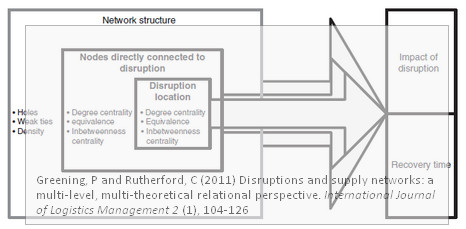

Conceptual framework

In the end, the authors develop the following conceptual network and hypotheses:

- The time taken for a network to recover will be greater in dense networks, compared to the time taken for less dense networks to recover.

- The impact of a disruption will be greater in less dense networks than in more dense networks.

- Disruptions in dense networks will result in greater instability across the network during the recovery phase.

- Networks with a higher proportion of holes, and associated high dependency ties, will experience greater disruptive impact on those networks with fewer holes.

- Networks with a high proportion of holes, and associated high dependency ties, will take longer to recover from a disruptive impact than those networks with fewer holes.

- Disruptions in structurally evolving networks will have greater impact than in mature networks with proportionately less holes.

- Nodes whose shortest connecting path to a disruptive event is via a weak tie will be impacted less than a node whose shortest connecting path is through a greater number of strong ties.

- Nodes whose shortest connecting path to a disruptive event is via a weak tie will recover more quickly than a node whose shortest connecting path is through a greater number of strong ties.

- The co-location of influence (as a result of degree or inbetweenness centrality) and disruption will result in greater impact than the location of disruption at nodes of lesser influence.

- The co-location of disruption and power will result in longer network recovery periods than the dislocation of disruption and power.

- Disruptions connected to powerful nodes (described by centrality) will result in less impact and then accelerated recovery period when compared to disruptions connected to less powerful nodes.

Conclusion

The objective of this paper, so the authors say, was to review the extant relational literature relating to networks, with a view to combining these theoretical perspectives with the literature surrounding supply chain disruptions. That they have done, no doubt about that, and this is one of the best articles on supply chain disruptions I have come across in a very long time. It is also a fine extension of the work done by Craighead et al. (2007), who came up with six propositions that relate the severity of supply chain disruptions to supply chain design characteristics and supply chain mitigation capabilities, and I’m definitely looking forward to seeing future research that builds on the work of Greening and Rutherford.

Reference

Phil Greening, & Christine Rutherford (2011). Disruptions and supply networks: a multi-level, multi-theoretical relational perspective International Journal of Logistics Management, 22 (1), 104-126 DOI: 10.1108/09574091111127570

Author links

- linkedin.com: Phil Greening

- cranfield.ac.uk: Christine Rutherford

Related posts

- husdal.com: Supply chain disruptions and network attributes

- husdal.com: Risk Management in Global Supply Networks

- husdal.com: SCRM Research – past, present and future

- husdal.com: Risk in supply networks