How are companies located in sparse transport networks affected by supply chain disruptions? This article develops a new framework for the categorization of supply chains, and introduces the notion of the constrained supply chain. Within the constrained supply chain framework, a company can address its locational disadvantage by either redesigning the supply chain towards a better structure, in order to gain better location, or by redesigning the supply chain towards a better organization, in order to gain better preparedness.

How are companies located in sparse transport networks affected by supply chain disruptions? This article develops a new framework for the categorization of supply chains, and introduces the notion of the constrained supply chain. Within the constrained supply chain framework, a company can address its locational disadvantage by either redesigning the supply chain towards a better structure, in order to gain better location, or by redesigning the supply chain towards a better organization, in order to gain better preparedness.

What are sparse transportation networks?

Disruptions of the transportation network as part of the supply chain are of particular interest in countries or regions with sparse transportation networks. Typically traits of such regions are few transportation mode options and/or few transportation link options for each transportation mode, for example maybe only one railway line and two roads, no port, no airport. With only a few transportation modes and links available between population centers, they become extremely vulnerable to any disruption in the transportation system or supply chain, since in a possible worst-case scenario no suitable alternative exists for deliveries to or from these communities (Dalziell and Nicholson, 2001; Berdica, 2002; Husdal, 2005; Jenelius et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2006; Husdal, 2009)

Why are sparse transportation networks important?

The question is, are businesses located in regions with sparse transportation networks in fact more prone to supply chain disruptions than businesses located in more favorable locations? Does a sparse transportation network in fact constrain the supply chain setup, such that it is more vulnerable and more likely to be disrupted? If this is the case, how do companies with constrained supply chains deal with their exposure to disruptions? What are typical disruptions in certain locations or for certain types of business, what is the cost associated with these disruptions, and how do companies counter or mitigate supply chain disruptions in their production planning, choice of supplier(s), choice of transportation mode(s), stockpiling and warehousing, and/or what contingency plans do they have? Do they focus on mitigation measures or on contingent solutions (Tomlin, 2006; Asbjørnslett, 2008)?

A framework for the categorization of transportation networks or supply chains

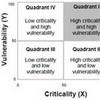

A supply chain that is subject to a sparse transportation network can not be structured freely, but is limited by constraints, mainly transportation mode choice (air, sea, rail, road) and transportation link choice within each mode. From this departure point, we can develop a new framework for the categorization of supply chains, based on the number of links and modes available in the transportation network, and establishes four principal types of networks or supply chains: Free, Directed, Limited and Constrained. In a free supply chain there are little or no constraints as to transportation modes and there is a dense transportation network with many possible links. In a directed supply chain there are many possible links, but few modes, thus directing the supply chain towards a certain mode or set of modes. In a limited supply chain there are many mode choices but few links, which creates an overall limited setup. In a constrained supply chain there are few choices as to mode and/or links and in worst case the supply chain is locked to one mode and very few, or maybe, only one link.

![]() Click image for larger version

Click image for larger version

A framework for risk and vulnerability in supply chains

The framework combines the notions on supply chain risk in Jüttner et al. (2003) and the notions in Craighead et al. (2007) that supply chain characteristics play a major role in supply chain disruptions. On one side a supply chain is exposed to certain risks, that may (or not) lead to certain supply chain disruptions. One the other side the supply chain has certain characteristics, which determine the supply chain vulnerability. The severity of supply chain disruptions is related to supply chain design characteristics (supply chain density, supply chain complexity and node criticality) and supply chain mitigation capabilities (recovery capability and warning capability). In brief: supply chain structure and supply chain organization. Within this framework, a company can address supply chain disruptions in two ways: 1) Redesign the supply chain towards a better structure, in order to gain a better location, or 2) Redesign the supply chain towards a better organization, in order to gain better preparedness.

Click image for larger version

Click image for larger version

A framework for overcoming locational disadvantage

Sparse transportation networks can be categorized as non-free supply chains and viewed as an unfavorable supply chain structure. By re-designing the structure, locational disadvantages can be lessened or entirely eliminated, and a supply chain wise “badly” located company can become “well” located. Conversely, if the structure cannot be improved (or not improved further), by re-designing the organization, proper training and adding supply chain visibility such that early warnings and early proactive and reactive actions are possible, a company can turn from badly prepared into well prepared. This may also be the case with favorably located (or supply chain structured) businesses that may have overlooked their preparedness.

Click image for larger version

Click image for larger version

Robustness – Flexibility – Agility – Resilience

Robustness, flexibility, agility and predominantly resilience (McManus, 2007) are key components in addressing unfavorable supply chains. The ability to survive (resilience) is likely to be more important in a business setting than the ability to quickly regain stability (robustness) or the ability to change course (flexibility or agility). A well-handled supply chain or transportation network disruption can translate into business continuity, while an ill-handled supply chain or transportation network disruption can translate into business dis-continuity, if not handled appropriately.

Supply chain life cycle

Overcoming unfavorable supply chains may be of particular interest in a supply chain life cycle perspective, where supply chains come into existence and cease to function as business opportunities come and go. A constrained supply chain setting may affect the ability to form new supplier and customer relationships (i.e. supply chains), and thus, this may limit the business opportunities for companies in said disadvantageous locations.

References

Asbjørnslett, B. (2008). Assessing the Vulnerability of Supply Chains. In G. A. Zsidisin & B. Ritchie (Eds.), Supply Chain Risk: A Handbook of Assessment, Management and Performance. New York: Springer.

Berdica, K. (2002) An introduction to road vulnerability: what has been done, is done and should be done. Transport Policy, 9(2) 117-127.

Craighead, C. W., Blackhurst, J., Rungtusanatham, M. J. & Handfield, R. B. (2007) The Severity of Supply Chain Disruptions: Design Characteristics and Mitigation Capabilities. Decision Sciences, 38(1), 131-156.

Dalziell, E. and Nicholson, A. J. (2001) Risk and impact of natural hazards on a road network. Journal of Transportation Engineering, 127( 2), 159-166.

Husdal, J. (2005) The vulnerability of road networks in a cost-benefit perspective. Paper presented at the TRB Annual Meeting, Washington DC, USA, 12 January 2005.

Husdal, J. (2009). Does location matter? Supply chain disruptions in sparse transportation networks. Paper presented at the TRB Annual Meeting, Washington DC, 11 January 2009.

Jenelius, E.; Petersen, T. and Mattson, L.-G. (2006) Importance and exposure in road network vulnerability analysis.Transportation Research Part A, 40, 537-560.

Jütner, U., Peck, H., & Christopher, M. (2003). Supply Chain Risk Management: Outlining an Agenda for Future Research. International Journal of Logistics: Research and Applications, 6(4), 197-210.

Taylor, M., Sekhar, S., & D’Este, G. (2006). Application of Accessibility Based Methods for Vulnerability Analysis of Strategic Road Networks Networks and Spatial Economics, 6 (3-4), 267-291

Tomlin, B. (2006) On the Value of Mitigation and Contingency Strategies for Managing Supply Chain Disruption Risks. Management Science, 52(5), 639-657.

Mc Manus, S. et al (2007) Resilience Management – A Framework for Assessing and Improving the Resilience of Organisations. Research Report 2007/01, Resilient Organisations, New Zealand.

Notes

Sparse transportation networks are a typical trait of much of the Norwegian road network. and the research described above is part of a research project at Møreforsking Molde / Molde Research Institute in Molde, Norway, and also part of my PhD research. In a study initiated by the Norwegian Public Roads Administration, a selection of manufacturing and production companies and transportation and logistics providers were surveyed and interviewed in order to investigate how companies located in sparse transportation networks are affected by and relate to supply chain disruptions. If you would like to know more about the project, please contact me.