Choosing the right supplier is a risky decision. Chose the wrong supplier, and you may face a severe disruption in your supply chain. Chose the right supplier, and all goes well. Hopefully. But is it possible to judge supply risk objectively? In the end, all risk decisions are subject to the decision maker’s perception of risk. The question is, does risk perception influence risk decisions? That is what Scott C Ellis, Raymond M Henry and Jeff Shockley try to answer in Buyer perceptions of supply disruption risk: A behavioral view and empirical assessment. Here they operationalize and explore the relationship between three representations of supply disruption risk: magnitude of supply disruption, probability of supply disruption and overall supply disruption risk. This is an article that hits right home they way I view risk.

Choosing the right supplier is a risky decision. Chose the wrong supplier, and you may face a severe disruption in your supply chain. Chose the right supplier, and all goes well. Hopefully. But is it possible to judge supply risk objectively? In the end, all risk decisions are subject to the decision maker’s perception of risk. The question is, does risk perception influence risk decisions? That is what Scott C Ellis, Raymond M Henry and Jeff Shockley try to answer in Buyer perceptions of supply disruption risk: A behavioral view and empirical assessment. Here they operationalize and explore the relationship between three representations of supply disruption risk: magnitude of supply disruption, probability of supply disruption and overall supply disruption risk. This is an article that hits right home they way I view risk.

Risk perception and risk decision

My interest in risk and risk perception goes back a long way. In 2001, while at the University of Utah, I wrote a course paper on issues in visualization of risk and vulnerability and how risk could and should be explored and presented in a visual manner to convey a clearer meaning to the decision maker. Today’s article does not look at risk visualization, but at risk perception and the behavioral process through which buyers make decisions in the face of potential supply disruption risks, i.e. the risk of a supplier failing to deliver, or in the worst case, a supplier defaulting. While a lot of supply chain risk research has gone into describing types of disruptions and their consequences, little research has sought to understand how views of supply disruption risk are developed and how these views affect the decision-making process. That is the core of the research I am presenting today.

Extensive groundwork

What I like very much about this paper is the extensive literature review on risk, risk perception and behavioral issues, drawing from a wide range of sources. They do not simply list references, but they take essential statements and link them together in a synthesizing manner, creating a fully interwoven background picture that leaves no gaps uncovered. From that they conclude amongst other things that

Managers do not view risk as prescribed by classical decision theory; instead, behavioral research suggests that perceptual rather than objective assessments of risk guide decision-making behavior.

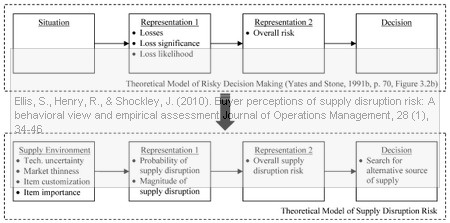

The authors transform and adapt a behavioral model of risk decision-making developed by Yates and Stone in Risk-Taking Behavior , where in contrast with the traditional risk management literature, there is a distinct difference between two successive stages of risk decision-making: judgment and evaluation. Individuals will first judge the probability of loss, the magnitude of loss, and other relevant considerations, and then evaluate overall risk. It is this appraisal of overall risk, not the probability or magnitude of loss that directly influences decision-making.

, where in contrast with the traditional risk management literature, there is a distinct difference between two successive stages of risk decision-making: judgment and evaluation. Individuals will first judge the probability of loss, the magnitude of loss, and other relevant considerations, and then evaluate overall risk. It is this appraisal of overall risk, not the probability or magnitude of loss that directly influences decision-making.

Theoretical model for referencing supply disruption risk

Using Williamson’s transaction cost economics theory and Pfeffer and Salancik’s resource dependence theory

, they identify four attributes of the supply environment that affect representations of supply disruption risk: technological uncertainty, market thinness, item customization, and item importance. Together with a four-stage behavioral model of risky decision-making, adopted from Yates and Stone, their model looks like this:

This is where it becomes interesting. While they still use the probability and magnitude of supply disruption as terms, they define them different from the traditional supply chain risk literature by adding the notion of perception:

The probability of supply disruption is the perceived likelihood that a supply disruption will occur.

The magnitude of supply disruption is the perceived severity of losses that may result from a disruption.

Consequently, the definition of overall supply disruption risk also has a notion of perceived risk:

Overall supply disruption risk is the individual perception of the total potential loss associated with the disruption of supply of a particular purchased item from a particular supplier.

The works of Yates and Stone provide much of the background for the authors’ view on supply disruption risk, and I can only concur when they suggest that the probability and magnitude of loss play a formative role in the development of risk perceptions. There is a distinct difference between judgement and decision, where a judgment is ‘‘an opinion about what is or will be the state of some aspect of the world’’. Overall supply disruption risk assessments, so they say, are driven by buyers’ judgments of the magnitude and probability of supply disruption they are facing. Essentially then, risk assessments are, if not flawed, at least seriously biased?

Hypotheses

- H1a. Probability of supply disruption is positively associated with overall supply disruption risk.

- H1b. Magnitude of supply disruption is positively associated with overall supply disruption risk.

- H2. The level of technological uncertainty is positively associated with the probability of supply disruption.

- H3. The level of technological uncertainty is positively associated with the magnitude of supply disruption.

Market thinness is the “the degree to which a buying firm has [a limited number of] alternative sources of supply to meet a need”. Thin markets reduce buyer alternatives because there are fewer suppliers, so

- H4. The level of supply market thinness is positively associated with the probability of supply disruption.

- H5. The level of supply market thinness is positively associated with the magnitude of supply disruption.

Item customization is the extent to which purchased items are modified according to the specifications of a specific buyer, and buyer specific adaptations to form, features, and/or fit enable customized components to enhance the internal or external quality of the buyer’s final product. However, a supplier’s failure to deliver customized items according to specifications can have significant negative consequences for the buying firm.

- H6. The level of item customization is positively associated with the probability of supply disruption.

- H7. The level of purchased item customization is positively associated with the magnitude of supply disruption.

Item importance represents the degree to which a purchased part is critical to the manufacture of an organization’s other parts, components, or end-products. If a component is important it naturally increases an organization’s vulnerability if acquisition of the resource is no longer assured.

- H8. The level of purchased item importance is positively associated with the magnitude of supply disruption.

As buyers perceive greater overall risk in the supply of a particular item from a specific supplier they will seek to reduce the risk by searching for alternative sources of supply.

- H9. Overall supply disruption risk is positively associated with the search for alternative sources.

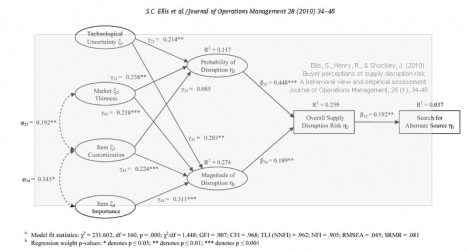

These hypotheses are then tested in a survey that returned answers from 223 direct material buyers and purchasing managers. The result can be seen below:

Click image for larger version

The full testing of the hypotheses, their correlations to each other, dependencies and independencies can be found in the paper, and is a very interesting exploration per se and well worth digesting. However, I will skip that here and head straight for the results.

Findings

Here are some of the most significant findings and my reactions:

Item customization and item importance affect the magnitude of supply disruption only, but not the probability of supply disruption.

This suggests perhaps a a focus on the effects more than the causes of supply disruption and that there is a greater weight on how to handle disruptions than how to prevent disruptions.

Product and market factors have differing effects on the probability and magnitude of supply disruption, suggesting that probability and magnitude are independent constructs.

To me, this suggests that relating to and comparing different probabilities is much more difficult than relating to and comparing different magnitudes.

The total indirect effect of market thinness and technological uncertainty on overall supply disruption risk is much greater than that of item importance and item customization.

This would indicate that the lesser influence a buyer has on specific product attributes, the greater is the perceived supply disruption risk.

The relationship between item customization and probability of loss is positive but not statistically significant.

The explanation given by the authors is that “buyers create self-imposed thin supply markets by purchasing customized direct materials that require suppliers’ specialized investment”, thus limiting the number of possible suppliers. In other words, a calculated risk the buyer is willing to take, hence the positive correlation.

Critique

As already mentioned, the best part of this paper is the extensive discussion of risk and risk perception that I have not seen to often in papers on supply chain risk. In fact, I do believe that this article may serve as a seminal paper to future researchers who endeavor to investigate behavioral aspects of supply disruption risk, because the model used can be easily adapted to include other contributing psychological factors, such as age, education, expertise, experience, cognitive ability, mood, recency of disruption, risk preference, problemframing, and prior success. While it will most likely not be my preferred research arena, I will definitely report on other papers I come across that follow up on the findings in this article.

Reference

Ellis, S., Henry, R., & Shockley, J. (2010). Buyer perceptions of supply disruption risk: A behavioral view and empirical assessment Journal of Operations Management, 28 (1), 34-46 DOI: 10.1016/j.jom.2009.07.002

Author links

- linkedin.com: Scott C Ellis

- clemson.edu: Raymond M Henry

- radford.edu: Jeff Shockley