Both shippers and motor carriers are impacted by travel time variability, but they react differently to it. While carriers focus on the immediate and short-term impact and how to solve the situation, .i.e how to deliver on time if still possible, shippers focus more on the strategic and long-term impact and on how to avoid the situation, i.e. how to prevent this from happening again. This is what Kelly Pitera, Anne Goodchild and Edward McCormack looked at in their recent paper titled Examining the Differential Responses of Shippers and Motor Carriers to Travel Time Variability. Here they describe the disparity in concerns and the strategies shippers and motor carriers are likely to engage in to address time travel variability.

Both shippers and motor carriers are impacted by travel time variability, but they react differently to it. While carriers focus on the immediate and short-term impact and how to solve the situation, .i.e how to deliver on time if still possible, shippers focus more on the strategic and long-term impact and on how to avoid the situation, i.e. how to prevent this from happening again. This is what Kelly Pitera, Anne Goodchild and Edward McCormack looked at in their recent paper titled Examining the Differential Responses of Shippers and Motor Carriers to Travel Time Variability. Here they describe the disparity in concerns and the strategies shippers and motor carriers are likely to engage in to address time travel variability.

Freight transportation and resilience

It is almost three years ago that I first blogged about the work of Kelly Pitera. I first met her at the TRB 2009 conference, where I presented my paper on supply chain disruptions in sparse transportation networks, and where she presented a paper on freight transportation resilience, a topic similar to my own research at that time. Her newest paper builds on her previous work, and the comparison of shippers versus carriers is very similar to what I did in my paper on how Norwegian freight carriers handle transportation disruptions. That said, Pitera’s work is much more thorough and academically sound than what I did.

Shippers versus carriers

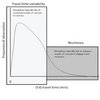

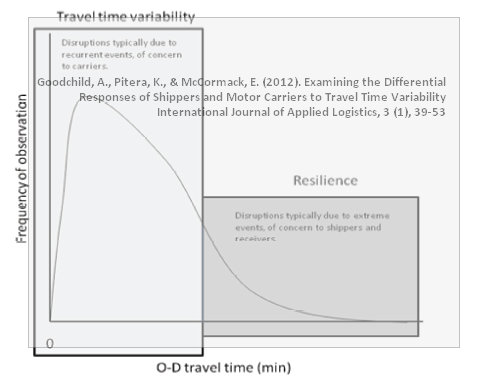

There is one figure in the paper that truly describes the difference in attitude that shippers and carriers have when it comes to travel time variability and disruptions:

The concern of the carriers are the day-to-day disruptions and delays that occur relatively often and which are a constant battle, but which are only a minor part of the overall travel time of the goods carried. The concern of the shippers is are the less frequently occurring disruptions that have a much greater impact on travel time and that can be avoided by careful planning.

The resilience triangle

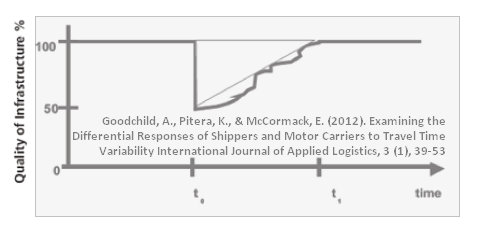

Another interesting concept from this article is the resilience triangle, originally published in Conceptualizing and Measuring Resilience A Key to Disaster Loss Reduction. This concept is a key framework for defining resilience and identifies the magnitude and duration of a disruption as two metrics by which resilience can be measured. The depth of the triangle illustrates the severity of the disruption, while the length of the triangle represents the time required for recovery.

As it says in the original article,

The “resilience triangle” in the figure represents the loss of functionality from damage and disruption, as well as the pattern of restoration and recovery over time. Resilience-enhancing measures aim at reducing the size of the resilience triangle through strategies that improve the infrastructure’s functionality and performance (the vertical axis in the figure) and that decrease the time to full recovery (the horizontal axis).

While the shape of the curve, the drop in performance and the return to normality can be seen in much of the literature on resilience, e.g. in Sheffi’s disruption profile, I have not come across the term “resilience triangle” before, but it is a term I think I will start using.

Shippers’ and carriers’ responses

Shippers and carriers employ different strategies for meeting travel time variability, and the authors identify these as the main differences:

Shippers:

- Flexible Transportation

- Distribution Center Network Structure

- Expedited Freight

- Use of Multiple Ports/Carriers

- Reducing Supply Chain Length

Carriers:

- Terminal Relocation

- Move delivery time

- Additional trucks

- Increased delivery time window

- Intersperse deliveries with strict requirements, with those that are flexible

This difference, so they say, can be partly explained by the market power of the shippers versus motor carriers and their ability to pass responsibility of day to day variability on to motor carriers.

Motor carriers are expected to manage the cost of congestion and regular delays, and need to internalize and absorb these costs into their business models. The customer (shipper) expects a certain level of service from the carrier and if this level is not satisfied, has the ability to change carriers. Often, it is the successful management of these frequently occurring disruptions that constitutes good service, thus the motor carriers have more motivation to develop strategies such as those mentioned above to address these types of disruptions.

This is not very different from what I found in my research on transportation disruptions, where disruptions and delays were not a major concern to transportation dependent businesses, i.e. those that contract the shippers, because as they saw it, the shippers knew how to handle whatever happened along the way.

Conclusion

This is a paper worth noting. The important takeaway from the paper is the linkage between shipper and carrier and the linkage between daily and not so daily travel time variability that connects these two players in the supply chain. In the authors’ own words,

Understanding the travel time variability response difference between these two members of the transportation system allows for recognition that improvements in day to day operations will benefit motor carriers first and if they reduce the cost of transportation may ultimately benefit shippers.

Essentially then, when it comes to supply chain disruptions, a bottom-up strategy is perhaps better suited than a top-down strategy.

Reference

Goodchild, A., Pitera, K., & McCormack, E. (2012). Examining the Differential Responses of Shippers and Motor Carriers to Travel Time Variability International Journal of Applied Logistics, 3 (1), 39-53 DOI: 10.4018/jal.2012010103

Author links

- linkedin.com: Kelly Pitera

- linkedin.com: Anne Goodchild

- linkedin.com: Edward McCormack

Related posts

- husdal.com: What is freight transportation resilience?

- husdal.com: How Norwegian carriers handle freight disruptions