It is a perpetual topic with the Norwegian public, particularly in election years, like this year: We want better roads. And indeed, it is puzzling that a country ranked as one of the world’s biggest oil exporters, a country whose economy is strong, a country ranked by the UN and OECD as one of the best countries to live in, has such a poor road standard, compared to many other European countries. How come?

It is a perpetual topic with the Norwegian public, particularly in election years, like this year: We want better roads. And indeed, it is puzzling that a country ranked as one of the world’s biggest oil exporters, a country whose economy is strong, a country ranked by the UN and OECD as one of the best countries to live in, has such a poor road standard, compared to many other European countries. How come?

The big question

Admittedly, the topography of Norway makes building roads, or any transportation infrastructure for that matter, quite a challange, but if other countries can pull it off, why not Norway? The answer, it seems, is a political one. It is not the planning authorities or the central government who decides, but the local politicians. To put it simple, what in the US is known as “pork barrel spending” is what rules many of Norway’s infrastructure development projects. Why?

Votes Count but the Number of Seats Decides

The first major discussion of this topic came in 2006, in Knut Boge’s PhD dissertation at The Norwegian School of Management:

Why has Norwegian authorities pursued a road policy contrary to most other West European industrialized countries? Why were highly noticeable congestion, accident and environmental problems within and near Norway’s major population clusters overlooked or ignored for decades?

The answer he says, lies in the way Norway decided about infrastructure investment, where prevalent legislator rule paved the way for a road policy governed by political rather than economic and technocratic logics:

Oil revenues made the Norwegian State nouveau riche from the early 1980s. But Stortinget (the Norwegian Parliament) shifted partly the State’s responsibility for financing trunk roads, motorways and other highways to the counties and private actors from 1985 through a pork barrel deal that imposed common turnpike financing. The 1963 Road Act that explicitly stated financing and construction of trunk roads, motorways and other highways as State responsibilities was not amended. Road financing through local turnpike companies instead of or in addition to State road appropriations made those who profited from turnpike projects important road political players.

What this implies is that local politicians have a much greater influence on infrastructure projects than in many other countries. Often there will be competing projects in nearby locations, and no oversight decision.

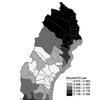

Geographical redistribution with disproportional representation

Knut Boge’s work was later followed up by professors Leif Helland and Rune Sørensen in their article Geographical redistribution with disproportional representation, stating that swing voters play an important role:

To some extent, individual districts are able to get their desired projects approved by parliament. But there is more to road investments than simple district demand. National parties allocate more road expenditures to districts with many voters and coordinate districts’ demands to win seats in parliamentary elections.

To sum it up, roads are not built where most people are, but where most voters are.

Conclusion

What is the result? The politically attractive projects win over the economically attractive (or sound projects).. From a cost-benefit perspective, mot of the time this is the wrong decision. And as long as our electoral system is the way it is, I don’t think it will change much. Unfortunately.

Another take on this story

(Update 2009/10/02) I recently discovered another blog posting on the exact same topic, and polemarchus.net provides a much better and probably more eloquent discussion Norwegian roads and swing votes than what I have given above.

The most disturbing point isn’t that the distribution of money is non-optimal from a cost-benefit perspective. That’s the nature of politics. The big problem is that there is a skewed distribution as a result of election strategy concerns. […] Valuing decentralized communities highly is acceptable from a democratic point of view. Consistently bribing swing voters with public money isn’t.

References

Helland, L., & Sørensen, R. (2008). Geographical redistribution with disproportional representation: a politico-economic model of Norwegian road projects Public Choice, 139 (1-2), 5-19 DOI: 10.1007/s11127-008-9373-z

Author links

- linkedin.com: Knut Boge

- researchgate.net: Rune Sørensen

- researchgate.net: Leif Helland

Links

- tu.no: Veikroner går til å vinne velgere

- aftenposten.no: Veikroner går til å vinne velgere

- aftenposten.no: Kraftige kutt i veibevilgninger

- polemarchus.net: Norwegian Roads and Swing Voters

Related

- husdal.com: Articles tagged with samferdsel

- husdal.com: Norwegian roads are so slooooow